470km journey from Leh to Manali. India. © Chetan Karkhanis / photos.sandeepachetan.com in association with TravelMag.com

2016 has been a bad year for India in terms of natural disasters. According to the study by the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED) the country has led the ranking of nations with the highest number of people affected, more than 331 million; it is followed by China, with 13, Ethiopia, with 10, Malawi, with 6.5 and Haiti, with 5.8. This classification developed by CRED records earthquakes, floods, drought, seaquakes, hurricanes and the rise of the sea level.

The overall number of affected people around the world has been 411 million, and therefore India gathers more than 80%. The reason for this difference is mainly due to the severe drought that has hit the country in 2016, which gives us an idea of the enormous climate vulnerability of the giant in Southern Asia.

Freshly cultivated paddy fields from Srinagar to Anantnag in Jammu and Kashmir, India. ©sandeepachetan.com travel photography

Dwindling water for a growing population

India´s population reaches approximately 1.335 billion inhabitants, practically twice the European population; what is more amazing is its birth rate (number of births for each 1000 inhabitants), which is 2.5, nearly twice the Spanish one (1.32). According to a report of the World Bank, should this growth rate continue, then India would have more inhabitants than China before 2035.

31% of the Indian population lives in cities and the remaining 69% lives in rural areas, with 80% of the population surviving mainly from agriculture and cattle, a figure well over the average rural population in Asia, which reaches 58%.

Therefore, a total of 921 million Indians have a tremendous reliance on renewable water resources that, according to AQUASTAT figures (FAO´s global information system on water), are around 1.431 m3 per inhabitant and year (nearly the volume of one and a half Olympic swimming pools). These figures are obtained by calculating the average rainfall, surface and ground water in a specific geographic area for periods of several years and dividing it by the number of inhabitants.

These statistics provide us an estimate of the water potential in each country. According to AQUASTAT, in Spain each inhabitant has, on average, 2.390 m3 of renewable water available (nearly two and a half Olympic swimming pools), while in Sweden, to mention an extreme example of disproportion, each inhabitant would have 17.660 m3 (more than 17 swimming pools) available. If we are concerned in Spain, with 46 million inhabitants, about the latest climate trends that predict a decrease in rainfall, in India, with 1.335 billion, the forecasts, also with a downward trend, are logically much more worrying.

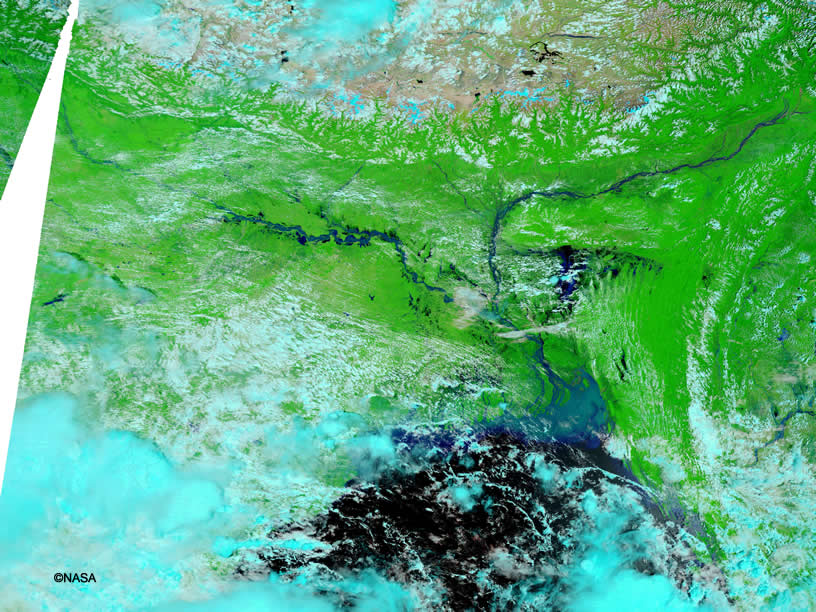

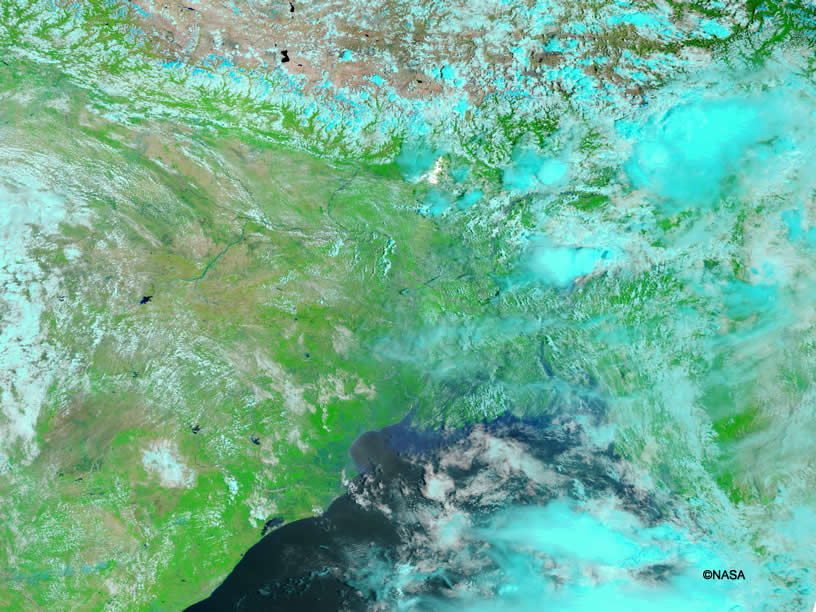

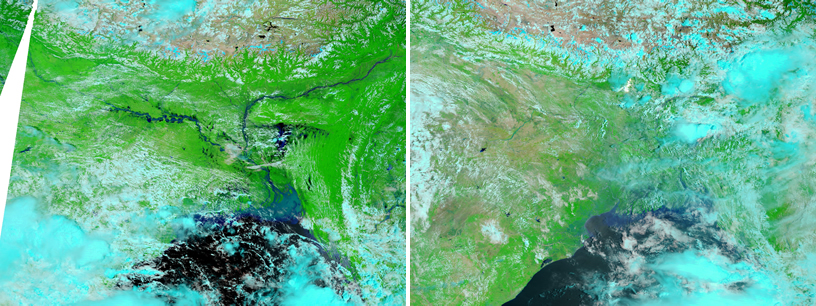

©NASA

Flooding in more than 1,000 villages in Bihar forced residents from their homes by late August 2011, the Indo-Asian News Service reported. After two years of drought, the Kosi River and Ganga (Ganges) Rivers were rising rapidly.

The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Terra satellite captured these images of a stretch of the Ganga, or Ganges, River around Patna August 30, 2011 (left), and June 23, 2011 (right).

Over-exploited aquifers and uncertain monsoons

In India the total area of cultivable land is of approximately 183 million hectares, more than 55% of the total surface of the country. In 2009, the cultivated area reached around 170 million hectares. These crops absorbed 688 km3 of irrigation water, a volume equivalent to over four times Lake Nasser, the reservoir at the Aswan dam, the third biggest in the world, shared by Egypt and Sudan. This equals 91% of the overall extracted water in the country, well above the world average, which is 69%. Another figure that confirms the vulnerability of the country to drought.

A further problem found in India´s agriculture is the over-exploitation of aquifers. The proliferation of wells, which have increased from 1 million in 1960 to 19 million in 2000, contributed notably to the alleviation of poverty, but has provoked a serious tension in the subsoil of certain areas where water is not regenerating and many wells are drying up.

Agriculture and most of the life in India depends on the climatic cycle of monsoons, which are winds with a thermal origin that behave in a very similar way to our coastal breezes, but on a much larger scale. The large Asian continental mass heats up in summer, making the air above it rise. The remaining void is filled with air placed on the Indian Ocean, cooler and full of humidity, which causes heavy rains, mainly as it is retained on the south side of the Himalayas. The flow of rivers rises dramatically and there are frequent floods. Exactly the opposite happens in winter: the drier and colder air from the continent moves towards the ocean. The superficial air above it rises as it is warmer, causing less rainfall.

The recharge of aquifers and especially rice and cotton farming rely on the summer monsoon. According to AQUASTAT this humid season discharges 80% of the annual 3.560 km3 of rainfall over India (in Spain, 322 km3). There are also important geographical differences in regard to monsoons: the northeast side of the country receives much more rainfall than all other regions, which are filled with uncertainty in the long droughts, like the one in 2016.

According to the Evaluation Report (AR5) of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) a decrease in rainfall and an increase in the number of summer days in which monsoons are interrupted have been predicted. An increase in extreme rainfall, the main cause of floods, has also been predicted, and there are already signs of it. Climate change comes with a bad omen for India.

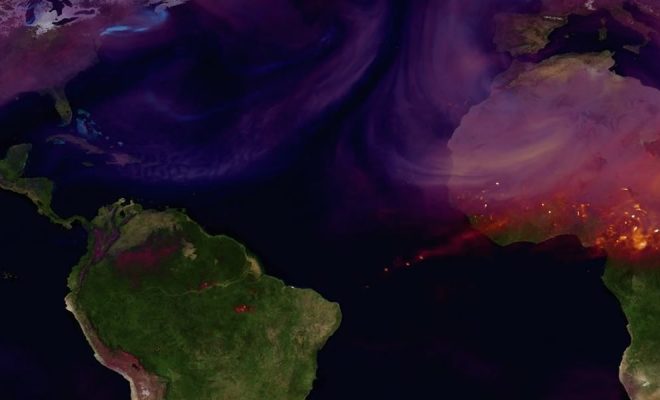

© NASA

According to Jeffrey Kargel, a USGS scientist, glaciers in the Himalaya are wasting at alarming and accelerating rates, as indicated by comparisons of satellite and historic data, and as shown by the widespread, rapid growth of lakes on the glacier surfaces. According to a 2001 report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, scientists estimate that surface temperatures could rise by 1.4°C to 5.8°C by the end of the century. The researchers have found a strong correlation between increasing temperatures and glacier retreat.

Looking out for glaciers and the rise of the sea level

Up to one third of the planet´s fresh water is in the form of ice in the Himalaya Mountains. This ice is one of the large water resources for the northern part of the country and an extraordinary water distributor between seasons. Specifically, the glaciers in the roof of the world feed the gigantic Ganges basin, where approximately 8% of the world´s population lives. After flowing for 2.510 km, the sacred river of Hinduism runs into the Bay of Bengal forming together with the Brahmaputra river, the greatest delta in the world and one of the agricultural areas with greater productivity and extraordinary biodiversity, and therefore it is also known as The Green Delta.

The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) calculates that these rivers that have their origin in the mountains in Nepal contribute to 70% of the pre-monsoon flow of the Ganges. A significant decrease in the volume of ice was detected in the peaks of the mountain range 15 years ago; specifically, the Gangotri glacier, where the river Ganges springs, decreases 23 metres in size every year.

But global warming does not only affect the flow of the river but also the rise in the sea level of the delta, which India shares with Bangladesh. According to AR5, a 0.5-metre rise of the sea level would make more than seven million people in the delta lose their homes, which are also threatened by floods, like the one in 1998, which left more than 30 million homeless people behind.

©Carlos Garriga/We Are Water Foundation

Horticultural development through drip irrigation systems in India. We Are Water Foundation project in collaboration with the Vicente Ferrer Foundation.

The giant reacts

India faces an immense challenge. The government of the country understands the importance and scale of the threat of global warming and therefore launched an ambitious National Action Plan on Climate Change in 2010, which establishes the strategy to follow in all industrial and energy sectors, placing particular emphasis on water resources and the agricultural and forest industry.

In May 2014, the Ministry of the Environment and Forests changed its name to Ministry of the Environment, Forests and Climate Change, which reflects the importance placed by the government on the need to face this challenge. In his speech on Independence Day in 2014, India´s Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, specially mentioned sustainable development and the respect for the environment. The government also attaches great importance to the cleanliness of rivers and has established a National Adaptation Fund on Climate Change and has created the Centre for Climate Change Research.

The development of solar energy is one of the foundations of the reform. India is placed in the so called “sun belt” and the obtaining of this renewable energy can also be planned for the water pumping stations. An example of the benefits of this technique can be found in the project that the We Are Water Foundation is developing in collaboration with the Vicente Ferrer Foundation in Anantapur. This and all other projects of the Foundation show some of the core ideas that need to be followed in India to adapt to climate change: better use of water with drip irrigation systems, collecting of rainwater and recovery of aquifers and building of adequate infrastructures for the collection and better use of water.

The Indian civilization has a beautiful example of balance with nature in its ancestral culture. Rivers, forests, mountains and species have been considered sacred according to old traditions, which worship the Earth as a mother. There is also proof that the country overcame an abrupt weakening of monsoons between 2200 and 2000 B.C., which the farmers overcame by adapting and diversifying their crops.

India´s challenge is the challenge of the planet. What happens there will have an impact on global sustainability in this century. All threats can be found there, but solutions lay there as well, and they will become the solutions for all of us.