This micro-documentary is the second in the series, following the one we produced in Guatemala’s Ceniza River basin about our intervention after the eruption of the Fuego volcano. You can find them both on our YouTube channel.

“Now that we have clean water, we are healthier than ever. It’s a big change in our lives.” Sarasua, one of the protagonists of the micro-documentary, used to drink from open sources shared with animals. In her community of Ambatosola, in Madagascar’s Androy region, she and the other women had to walk several kilometres to the foothills of the mountains to bring water home. Beyond the time lost, that water was a source of intestinal diseases that impoverished their families and hindered their children’s education.

For the past two years, Sarasua and the other women in her community have had access to one of the ten wells we built with UNICEF in Ambatosola and Mahasoa. “Our tummy used to hurt,” she recalls in the micro-documentary. “Now the water keeps us clean.” The rest of the community has also benefited: farmers were worn out from having to fetch water every day to irrigate their crops during the dry season.

Sarasua, one of the protagonists of the micro-documentary, and the other women in her community of Ambatosola, in Madagascar’s Androy region, walked several kilometres to the foothills of the mountains to bring water home.

An Almost Forgotten Island

The micro-documentary reveals a harrowing issue for Madagascar. The largest island in Africa and the fourth-largest in the world, with a population of 31 million, faces severe shortcomings in access to water and sanitation.

According to the latest data from the JMP — the Joint Monitoring Programme of WHO and UNICEF — Sarasua and the more than 3,000 project beneficiaries relied on water sources technically classified as “unimproved”, meaning they offered no guarantee of safety. Across the country, nearly 10 million people are in the same situation. Worse still, around three million people have no choice but to use surface water — including rivers, reservoirs, ponds, irrigation canals, or ditches — with the associated health risks.

Another telling figure: more than one and a half million Malagasy people do have access to drinking water, but only if they walk more than 30 minutes to the nearest source. Altogether, nearly half of the population (some 14.6 million people) remain far from enjoying the Human Right to Water, as defined by the United Nations. The UN Development Programme (UNDP) has warned, particularly since the COVID-19 pandemic, of the country’s “low human development” status.

In 2023, Madagascar recorded a Human Development Index (HDI) value of 0.487, ranking it 177th out of 193 countries evaluated and indexed by UNDP.

In the micro-documentary, Carlos Garriga highlights the significant improvement in schooling brought about by access to water — a crucial factor if the country is to break free from the scourge of extreme poverty. Since 2000, progress has been steady but slow: expected years of schooling — that is, the number of years of formal education a child entering school can expect to complete in their lifetime — have risen from 7.6 in 2000 to 9.9 in 2024.

In the micro-documentary, Carlos Garriga highlights the significant improvement in schooling brought about by access to water.

Sanitation: Ending Open Defecation

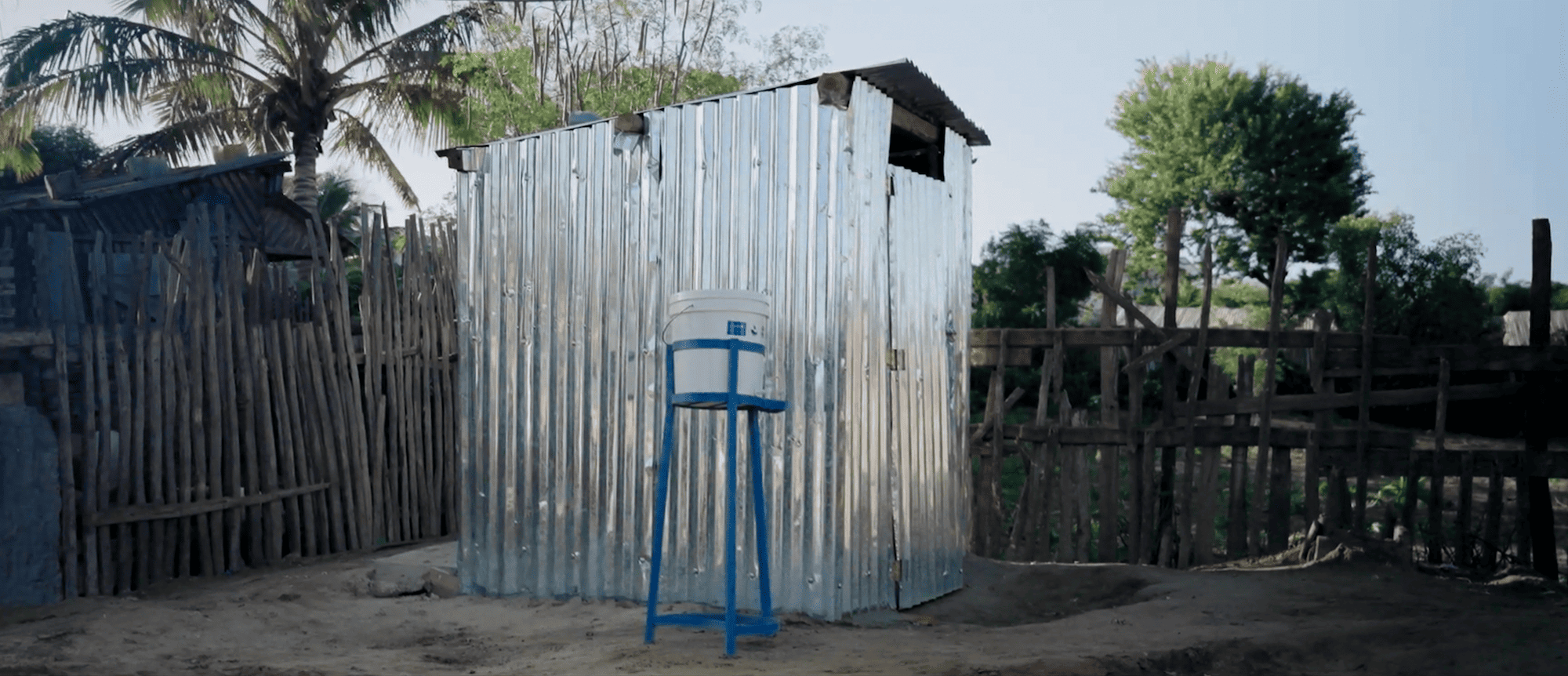

Our intervention in Madagascar also included a pilot project to build safe latrines in Bekily, one of the areas where open defecation was common due to the precarious and dilapidated state of existing facilities.

Following our Manual for the Construction of Latrines and Wells, a practical guide designed to be accessible to millions of users without prior training in sanitation, more than 200 people have been able to abandon the degrading practice of defecating in the bush. “Our daily life is better: we now have proper latrines and can relieve ourselves cleanly, safely and close to home,” explains one of the community leaders. “The future of our children looks brighter than before. Now we can raise them in better conditions.”

The success of this pilot project is a model to be replicated in Madagascar, where in 2024 more than 8.6 million people still practised open defecation and around 11 million lacked hygienically safe facilities — that is, simple pit latrines without a slab or platform, hanging latrines or bucket latrines, with no guarantee of avoiding contact with faeces and no facilities for handwashing.

Carlos Garriga stresses that, in Madagascar, we have continued to apply a fundamental principle in ensuring access to sanitation in any community: “the integration of facilities with their surroundings and the acceptance of the type of latrine by the whole community.” This principle has been applied and refined over the past 15 years in the 65 sanitation projects that have benefitted more than 2.6 million people in the areas of greatest need across Africa, Asia and the Americas.

Our intervention in Madagascar also included a pilot project to build safe latrines in Bekily.

Visit and subscribe to our YouTube channel.