It may seem paradoxical that a physiological act as fundamental for human health as defecation cannot yet be performed safely by 3.6 billion people all around the world and continues creating profound differences between wealth and poverty, development and stagnancy, health and disease, dignity and shame. The fight to eradicate these scourges is being waged on very different fronts marked by geographical, cultural and political differences. Each case calls for specific strategies, but they share a common context: investing in making defecation a hygienic act that ensures the health of people and the environment is both a human necessity and a source of profit.

This context was introduced by Laura Korčulanin, facilitator of the webinar “Valuing toilets beyond visible”, organized by the We Are Water Foundation within the framework of World Toilet Day, in collaboration with Roca Lisboa Gallery and the Give a Shit Project.

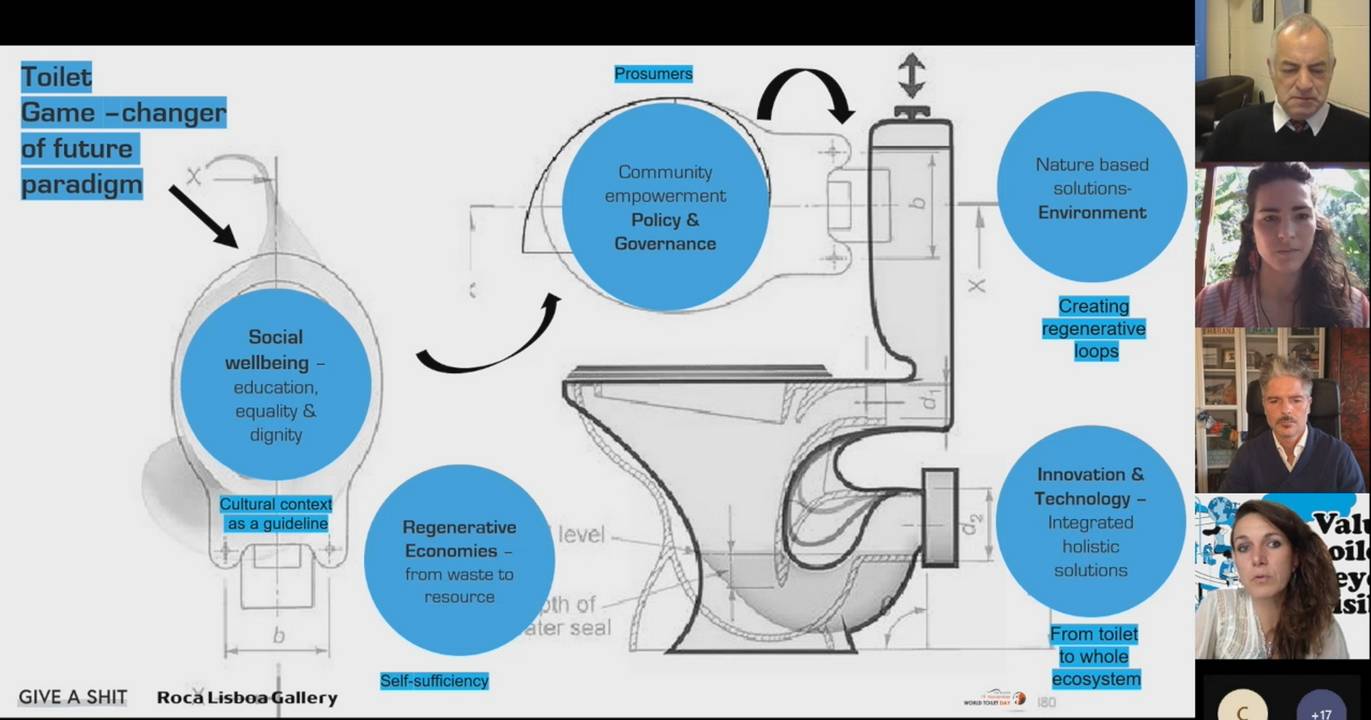

Laura Korčulanin, the founder of Give a Shit stressed the need for a new toilet paradigm that allows for investment and innovation to achieve inclusivity for all communities.

Korčulanin, founder of the Give a Shit international project and researcher at the Faculty of Design, Technology and Communication of the European University (IADE-UE) in Lisbon, introduced three experts in the fight for access to sanitation who explained three success stories, each one of them being a road map to attain the SDG 6 by 2030: Mona Mijhtab, founder of Mosan Sanitation Solutions, who works to improve the living conditions of remote communities by providing access to autonomous sanitation services; Graham Alabaster, Chief of Sanitation and Waste Management at the Urban Basic Services Branch of UN-Habitat, an expert in developing access to sanitation solutions in African slums; and Carlos Garriga, director of the We Are Water Foundation, who recently, together with UNICEF and the Government of Burkina Faso, has succeeded in eradicating open defecation in the Burkinabe province of Sissili and is currently working to expand its success to the entire country.

Defecation, toilets… uncomfortable concepts that must be faced

The problems of poor sanitation related to human defecation are socially awkward, even though defecation is an act shared by all humans. Nowadays, where and how people defecate makes a significant difference between well-being and poverty, a difference generated around the toilet, a basic facility for global sanitation. Having or not having a toilet greatly affects living conditions, and it is as important as having access to drinking water and food. Having a private toilet, which allows its users to avoid any contact with feces and removes them without polluting the environment is not only an unquestionable human right, but also a need that affects the sustainable and fair development of humanity.

Korčulanin recalled the social discomfort everyone experiences when talking about defecation and toilets, while pointing out the paradox of the unimaginable lack of investment in sanitation: “Every dollar invested in basin sanitation has a return of up to 5 dollars in saved medical cost, while increasing productivity and generating jobs along the entire service chain,” she said.

The founder of Give a Shit stressed the need for a new toilet paradigm that allows for investment and innovation to achieve inclusivity for all communities and end the scourge of child diarrheal diseases that kill increasing numbers of children under the age of five.

Carlos Garriga, director of the We Are Water Foundation, explained the 11-year experience of the We Are Water Foundation in sanitation projects and pointed at the interrelationship that almost always exists between the lack of water supply and sanitation.

Towards the total eradication of open defecation

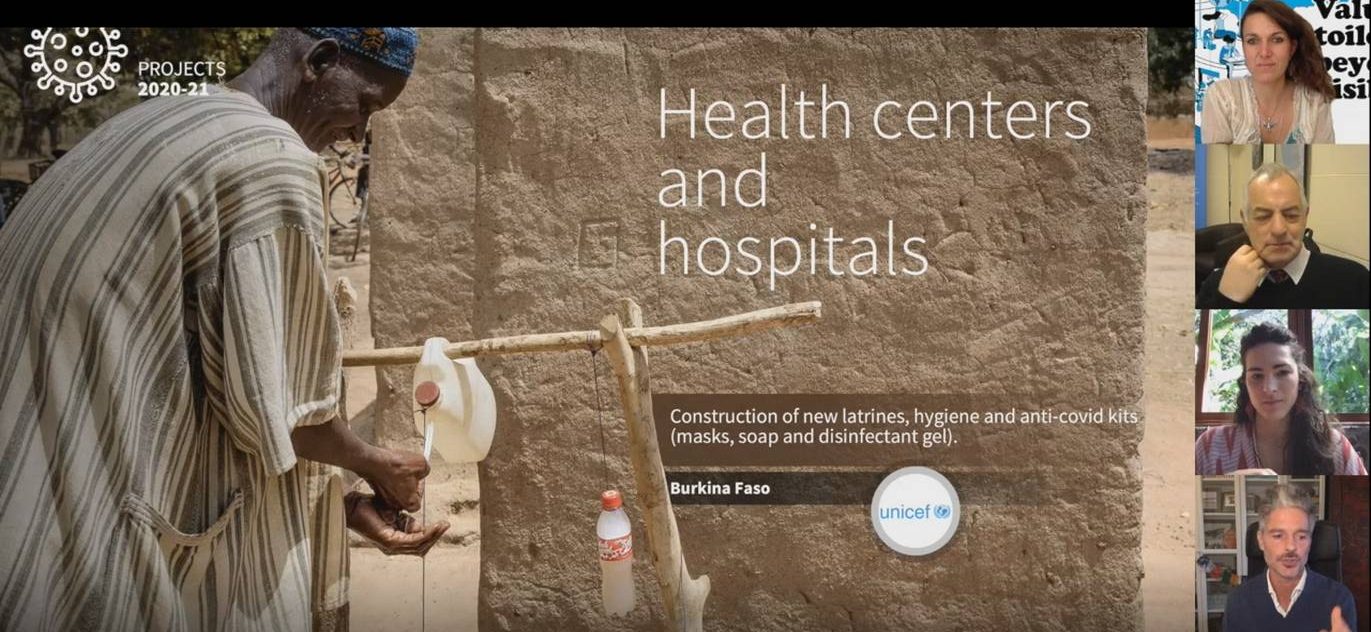

Carlos Garriga explained the 11-year experience of the We Are Water Foundation in sanitation projects and pointed at the interrelationship that almost always exists between the lack of water supply and sanitation, which results in the lack of hygiene: “Without water, hand washing is impossible,“ he commented, which has been evident during the Covid-19 pandemic, during which the Foundation has carried out projects in especially vulnerable areas and contexts, such as schools, migration border areas, hospitals and neglected rural regions.

Of particular relevance as a success story in the context of World Toilet Day is the Foundation’s work in Burkina Faso, one of the poorest countries in Africa. There, the collaboration with UNICEF started four years ago has succeeded in eradicating open defecation in the Sissili province, by implementing the CLTS method. This method is based on the empowerment of communities who, through self-awareness of the serious consequences of open defecation, decide to abandon this practice and build their own latrines.

The development of the Manual for the construction of latrines and wells, a volume that compiles the experience accumulated in the Foundation’s sanitation projects all around the world, established one of the working bases supported by the Ministry of Water and Sanitation and the Ministry of Health in Burkina Faso.

The success and experience gained led the Burkina Ministry of Water and Sanitation to consider close collaboration with the Foundation with the aim of making the entire country open defecation free.

Mona Mijthab, founder of Mosan Sanitation Solutions, explained the development of Mosan: a system with no connection to the water supply network that can operate without water or chemicals.

Autonomy and no connection to the network is empowerment

Mona Mijthab, founder of Mosan Sanitation Solutions, with extensive experience in access to sanitation all around the world, then explained the development of Mosan, a circular regenerative system, in Guatemala, a country with six million people lacking safe sanitation and specifically in the communities of Lake Atitlán, where 500 liters of untreated wastewater are discharged every second.

Mosan is a system with no connection to the water supply network that can operate without water or chemicals. Each household collects its excreta in a simple latrine and then hands them over to a person who transports them manually to a collection center to take them to a processing center. There the urine is processed by precipitation, obtaining struvite and feces are transformed by pyrolysis into biochar (plant-based biomass). The resulting mass is transferred to a reactor which carbonizes it for safe reuse as fertilizer.

Mosan Sanitation Solutions has partnered with the Ministry of Agriculture of Guatemala to roll out its technology nationwide. One of the main challenges is to find a way to make the project financially viable; one possible way is for families to pay a small monthly fee. Mona Mijthab is confident that the project’s own philosophy and the success of the solution in the Lake Atitlán communities will facilitate its expansion: “We have been inspired by the living conditions of the people and have prioritized them to make the system sustainable. The community must be fully involved and lead the sanitation projects to take ownership of the solutions so that everything works in the long term”.

Graham Alabaster, UN-Habitat expert, presented a case study in which they used access to water and sanitation as an entry point for improving the Kibera slum in Nairobi. © SuSanA Secretariat

Slum roads

Graham Alabaster explained the sanitation problems in urban slums, where it is very difficult to provide water and sanitation services, and where high population density and poor quality housing are critical to health. The UN-Habitat expert stressed the importance of understanding communities and providing services that fit their customs, and of being able to provide solutions that improve living conditions beyond the sanitation services themselves.

In this regard, Alabaster presented a case study in which they used access to water and sanitation as an entry point for improving the Kibera slum in Nairobi, one of the largest in the world and where UN Habitat estimates that between 500,000 and 800,000 people live in shacks that are rarely more than 12 square meters in size.

Alabaster explained that the community was interested in having a road into the slum, as well as communal facilities. The construction of the road made it possible to install water and sanitation access points, as well as an open space where people could gather and walk around, and to facilitate the development of other possibilities such as the collection of rubbish and solid waste for recycling. “Using water and sanitation as an entry point for slum upgrading had different impacts, all very positive,” Alabaster pointed out. “The overall result is a change of life that ensures the sustainability of the project. We are going to use this idea of building the roads in combination with water and sanitation infrastructure in another slum in Nairobi.”

Learning from success stories is the best way forward. The challenge of achieving SDG 6 by 2030 is daunting. There are many variables and circumstances that make the path to making defecation a hygienic act very complex. But all solutions require the rightful participation of communities, from their self-awareness to their empowerment in managing the solutions. This is the way to make this inescapable human right a source of wealth that benefits us all.