Arid or dry areas, without a uniform vegetation cover or a very uneven one, were estimated that year at 40% of the Earth’s surface. © Hu Chen-unsplash

In 2015, the forest area estimated by FAO was of around 4,06 billion hectares, 31% of the Earth’s surface, the equivalent to almost one soccer field per person. 45% of this surface corresponded to the forest mass in tropical areas: mainly the large African, South American and Indonesian jungle extensions. Arid or dry areas, without a uniform vegetation cover or a very uneven one, were estimated that year at 40% of the Earth’s surface.

For public opinion, the importance of trees globally has been traditionally absorbed by forests. They have been given the leading role in the fight against global warming as they are the main carbon sink, regulating climate and being essential in the atmospheric water cycle. It is mainly for this reason that at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), which took place in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, scientists, alarmed by the excess of CO2 in the atmosphere, established the preservation of forests as a priority goal. Since then, society has focused on the evolution of the large forest mass, mainly the tropical one, considered the planet’s “lung”, which was in danger.

Obvious but little known

“Tree outside the forest”, “scattered forest” or “scattered trees” appeared: an extremely important factor in the fight against desertification. © Tobias Mand.

In 1995, this approach started to change when an increasingly larger group of geographers, economists, urban planners and climatologists highlighted the importance of the tree itself, placed in a context that was isolated from the forest mass. The neologisms “tree outside the forest”, “scattered forest” or “scattered trees” appeared, which gradually became more present to designate an extremely important factor in the fight against desertification and soil management, whether agricultural, peri-urban and urban.

In 2002, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) published the study Trees outside the forest. Towards a better awareness, which had been commissioned from a multidisciplinary group of experts. It defined and laid the groundwork for a categorization of trees outside the forest according to their relevance to agriculture, land management and culture; and emphasized their importance for climate regulation, land planning and food security, as well as landscape management, a psychosocial factor usually neglected in the assessment of people’s well-being.

FAO’s alert was the seed that led to research on this type of vegetation, as the amount of information available until then had been scarce, almost always of a local nature and with a limited scientific base. Satellite observations made at the beginning of this century provided images with a resolution of only 30 meters. The system was better than those used until then, but still insufficient. With that resolution, if two or three trees existed in a diameter of less than 30 meters, they were counted as one, or none; also during the dry season or in their deciduous phase (without leaves) many trees were invisible to the satellite cameras.

A key to dry land knowledge

Scattered trees have been crucial for rural economies and vital for the survival in arid regions.© Carlos Garriga/ We Are Water Foundation.

As anthropogenic global warming became evident, the importance of studying vegetation spread among the scientific community. In particular, knowing the status of trees in the arid zones of tropical regions, which are often transition zones between humid tropical and desert climates, became a priority in view of the threats of increasing droughts and violent weather events. Many of these areas are often home to some of the world’s poorest regions and the most vulnerable to extreme weather events.

A second important step was taken in 2014, when FAO launched the Global Dryland Assessment to better understand the extent of scattered trees in areas threatened by desertification and lay the groundwork for a better monitoring of their condition. The project, which involved more than 200 researchers including scientists and students, was based on the detection power of the WorldView-3 satellite, which reached a resolution of 25 cm (!), and on the use of the Collect Earthtool, which allows data collection through Google Earth or Bing Maps.The study was presented in May 2017 in Rome and its articleThe extent of forest in dryland biomes was the cover of the Science magazine of that month.

More trees than previously thought

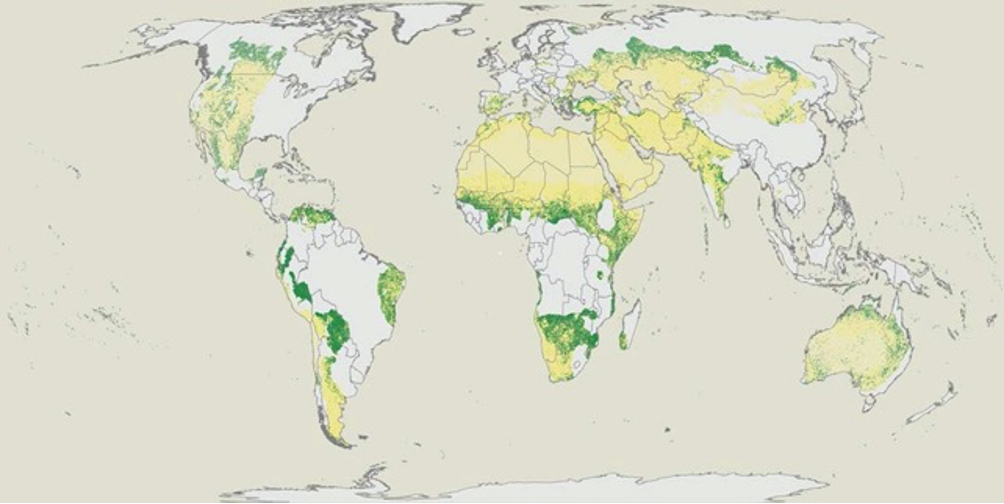

After evaluating the satellite data, it was found that the arid zones had 1,327 million hectares of trees, an increase of 40-47% of the forest cover estimated before the study for arid areas, thus increasing the global area of existing forests on the planet by 9%. The area of this scattered forest mass in arid zones is equivalent to that of the Amazon, and therefore plays a very important role in the global fixation of CO2.

Presence (green areas) and absence (yellow areas) of trees in arid regions of the Earth. @ Bastin et al., Science 356,635 – 638 (2017)

The discovery of this active biome reaffirms the importance of trees outside forests for the study of climate evolution and desertification and for a better planning of agricultural land management in the most troubled areas due to their endemic poverty, such as African, Asian and Latin American drylands.

Saving the “guardians of water”

The baobab’s key feature is its capacity to retain water. © Yasmine Arfaoui -unsplash.

An example could be the study of the health of certain key trees in these areas such as, to mention the best known example, the African baobab (Adansonia digitata), whose oldest specimens are suffering an alarming mortality rate, as warned by a recent study led by botanist Adrian Patrut of the Babes-Bolyai University in Romania.

Baobabs are long-lasting trees (800-1,000 years, some specimens reaching 2,000 years or more) and fundamental to the ecosystems where they grow; its fruits provide food, valuable micronutrients and natural medicine to people and animals, such as elephants, scatter their seeds thereby contributing to their reproduction.

However, for humans, the baobab’s key feature is its capacity to retain water. The tree can store it in its roots and fibrous trunk during the rainy season. According to Patrut, the highest baobabs can reach 30 meters and store more than 130,000 liters of water to survive during the dry season. That water has been a treasure for indigenous people since time immemorial, which explains why many call the baobab “guardian of water” or “tree of life”.

The study by the Romanian researcher confirms the decrease in the number of baobabs and although it does not explain why this is happening, it suggests that the climate alteration we are currently experiencing might be the cause, as the tree’s life and evolution is closely linked to water and evapotranspiration.

Satellite tracking of scattered trees can be a valuable tool to assess the decrease rate of baobabs, the areas of greater occurrence and to diagnose the cause of the decrease in the number of trees.

Like baobabs, other scattered trees in dry areas are water ambassadors in aridity and therefore extremely valuable. In Brazil, the roots of the Buruti palm tree stand out, as they spread water over the surface of the thirsty land. The animals and people from the savannah, when they are thirsty, are guided by the unmistakable profile of this palm tree.

The candelabra tree, in the African Savannah, for instance, is essential for the balance of ecosystems. © Mindy McAdams.

En las sábanas africanas, las acacias, el árbol de baya chacal (diospyros mespiliformus) y el árbol candelabro (euphorbia ingens), por ejemplo, son fundamentales para el equilibrio de los ecosistemas y de los pueblos que habitan entre ellos. También muchas veces no se valoran suficientemente las encinas, pinos, alcornoques y sabinas en la cuenca mediterránea, ni los tilos, plataneros y almeces que dan sombra y oxígeno en muchas ciudades de los cinturones subtropicales, secundan carreteras, retienen la tierra y drenan el agua.

Every tree counts, and those outside the forest do so in a special way.© Simon Rae-unsplash.

The SDG 15 calls for protecting, restoring and promoting the sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, i.e. fostering “life on land”. Every tree counts, and those outside the forest do so in a special way.