The United Nations Conference on Biological Diversity, known as COP15, was held from December 7 to 19 in Montreal. It brought together governments from around the world to agree on new targets for global action on nature until 2030.

COP15 was held three weeks after COP27, the United Nations Climate Conference in Sharm el-Sheikh. COP27 addressed measures under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and how to adapt to these changes. At the same time, COP15 in Montreal focused on life on Earth as established by the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), a treaty signed by 150 government leaders at the 1992 Rio Earth Summit.

Conceived as a practical tool for turning the principles of Agenda 21 into reality, the CBD treats biodiversity as a concept beyond flora, fauna, and their ecosystems: it focuses on people and our need for food security, health, clean air, clean water, and housing, elements closely linked to the balance of the biosphere.

COP15 on biodiversity has been the first in which the private sector has participated. © UN Biodiversity.

The private sector as an essential asset

COP15 in Montreal marked a significant turning point as the first in this series of summits to involve the international private sector. This is a realistic and practical breakthrough. Public or private companies are organizations that provide goods, services, and jobs to people. They link civil society directly to nature, which provides raw materials and energy. This link is what moves the world and is essential to ensure success in the race towards the SDGs in 2030 and to achieve the vision agreed upon by all participating countries that humanity should live in harmony with nature by 2050.

The meeting was therefore divided into two blocks: political delegates, who discussed the preparation of a draft agreement, and groups of companies and civil society organizations from various countries who, in a more practical way, set out their objectives based on the progress made in biodiversity. This second group, the largest, was responsible for the most encouraging figure of the Conference: nearly 25,000 people came to discuss and press for action, the highest attendance figure in its history, close to that of COP27 in Sharm El Sheikh.

The biosphere is suffering, and we must heal it

Even before the symptoms of climate change became apparent, biodiversity was already showing evidence of its deterioration. In the last decade, many scientific studies have warned about it. The UN claims that around one million species of animals and plants are now threatened with extinction, and native species in most major terrestrial habitats have declined by at least 20% since 1900. At least 680 vertebrate species have become extinct since the 16th century, and in 2016, more than 9% of all domesticated breeds of mammals used for food and agriculture disappeared from the Earth.

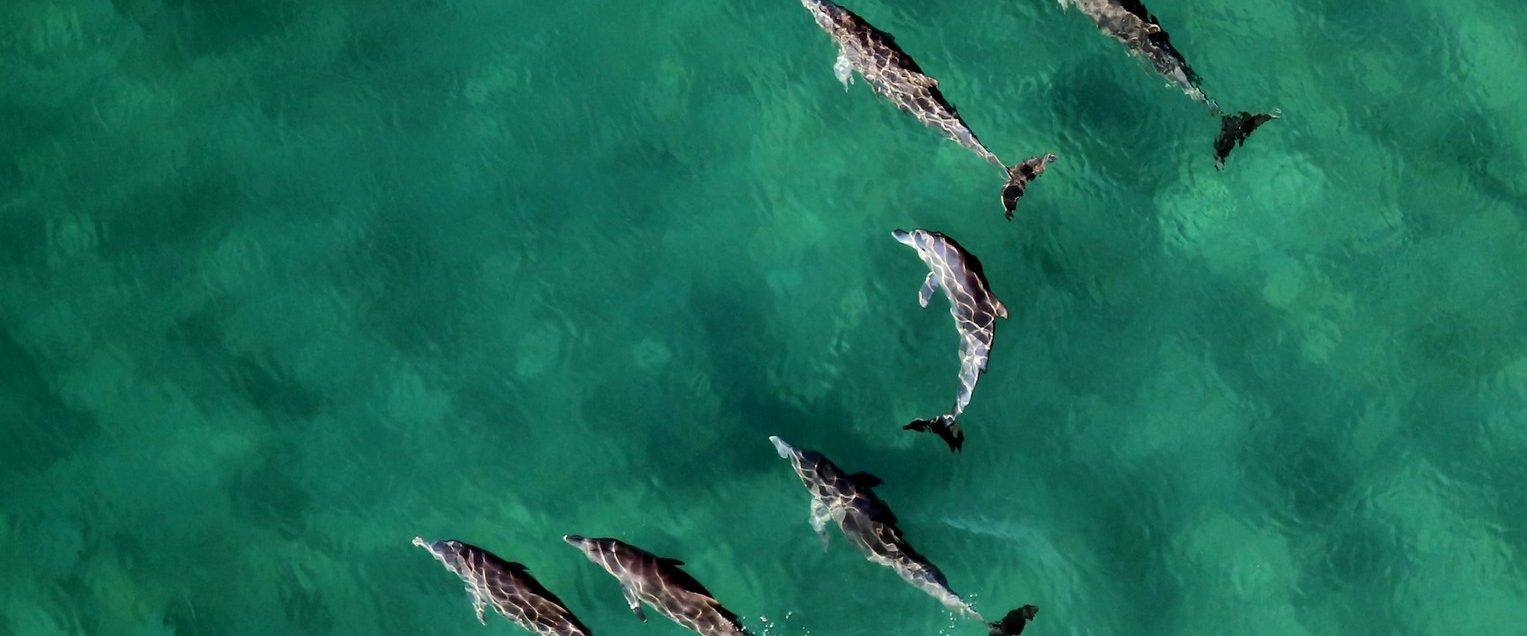

The outlook for the future is not encouraging: around 41% of amphibian species, almost 33% of reef-building corals, and more than a third of marine mammals are threatened. As for insects, the key to processes such as pollination, it is estimated that 10% are threatened.

With these data, and similarly to the opening of COP27, the UN Secretary-General, António Guterres, was categorical: “Today we are not in harmony with nature; on the contrary, we are playing a very different tune, a cacophony of chaos played with instruments of destruction.” And he went so far as to describe humanity as “a weapon of mass extinction” that “treats nature like a toilet.”

The outlook for the future is not encouraging: around 41% of amphibian species, almost 33% of reef-building corals, and more than a third of marine mammals are threatened. © Wynand Uys – unsplash

Companies understand natural capital

Many representatives of the most important multinational companies in attendance gave reason for hope. There is at least a consensus in admitting that the deterioration of natural capital is a risk to business investment. There is now a clear opportunity for financial flows to fuel positive goals for nature. All economies and industries depend directly or indirectly on natural cycles, and no business can afford to ignore their value.

In this regard, the presence at COP15 of the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD), which has been developing a joint roadmap since 2010 to ensure that companies are part of this transformation by 2050, took on particular relevance. The association advocates in the document Vision 2050: Time to transform the idea that more than 9 billion people, the estimated population of the Earth by 2050, will be able to live well within the limits of nature. To achieve this, the WBCSD advocates a transformation at scale in which companies focus their actions on areas through which they can lead the change.

The UN highlights the most important ones, in which the safeguarding of water is fundamental: one of them is to conserve worldwide at least 30% of terrestrial, marine, and coastal areas so that they are effectively managed through systems of protected areas © Aaron Burden-unsplash

The most ambitious plan for 2030

The negotiations in Montreal concluded with the adoption of the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework, conceived as the most ambitious global plan ever developed for the environment. The draft is structured through four significant goals and sets 23 specific targets for 2030 that are complemented by the 17 SDGs. The UN highlights the most important ones, in which the safeguarding of water is fundamental:

- Conserve worldwide at least 30% of terrestrial, marine, and coastal areas so that they are effectively managed through systems of protected areas.

- Restore at least 20% of the world’s degraded freshwater, marine, and terrestrial ecosystems.

- Halve the rate of introduction of invasive species. A problem that mainly affects aquatic ecosystems.

- Reduce by at least 50% the nutrients lost to the environment, causing eutrophication in water, and by at least 60% the chemicals, particularly agricultural pesticides, that are wreaking havoc on biodiversity.

- Eliminate the dumping of plastic waste in rivers and seas.

- Minimize the impact of climate change on biodiversity and contribute to mitigation and adaptation through nature-based solutions.

- Mobilize at least $200 billion annually in domestic and international funding for biodiversity in developing and resource-poor countries, which generally have the most extraordinary planetary biodiversity.

The concept of natural capital needs more specificity to be understood. A clear example is the need to stop the overexploitation of aquifers and the pollution and drying up of wetlands that jeopardize the agricultural future of millions of people and thousands of companies around the world. © Alex Smith – unsplash

“Change starts from the bottom up”

One of the most exciting conclusions of COP15 is the reversal of the principle that “change starts from the top,” in the sense that the achievement of a global agreement has the power to drive regional and national policies that are the ones that incentivize “downward” investment interest and the consequent transformation of companies.

It was already evident at the last COP27 that the picture is reversed due to the “upward” pressure exerted by civil society and the private sector: on government representatives. Business representation and activity in Montreal came from a wide range of industrial sectors that are demanding more clarity and pragmatism from the political power on the safeguarding of biodiversity.

The concept of natural capital needs more specificity to be understood by the public and many economists. A clear example is the need to stop the overexploitation of aquifers and the pollution and drying up of wetlands that jeopardize the agricultural future of millions of people and thousands of companies around the world.

Natural capital is the origin of the generation of all the resources that drive our economy. Its preservation is critical for the fight to mitigate climate change to be effective and for us to adapt with guarantees of resilience. We are part of nature; saving it means saving ourselves.