Covid-19 precautions in Mali. © World Bank / Ousmane Traore

To paraphrase Mario Benedetti, when we thought we had all the answers, the coronavirus pandemic has suddenly changed all our questions. This is especially evident in the field of architecture and urban planning. It is no longer just a question of optimizing resources, reducing pollution and ending slum poverty; we must now also respond to a threat we believed to be anachronistic: contagion.

Massive contagion is inherent to an essential characteristic of cities: density. Agglomeration in space is the raison d’être of cities; it is what generates their economic and cultural wealth. The proximity between individuals, the wrongly called “social distance” in this crisis, whether for living, working or relating, is an inherent characteristic of the systems of production of goods and services, especially after the Industrial Revolution. Demographic density and contagion are now priority factors in strategies to combat Covid-19 and are particularly relevant in view of the reports, endorsed by the World Health Organization (WHO), which warn that pandemics will be an inevitable factor in the future of humanity if it does not grow in a way that is balanced with the environment.

The health crisis has erupted at a time when architects and urban planners are engaged in a profound debate on how to move efficiently towards sustainability. The questioning of the urban model is not new, it has been inherent in cities since they were born 8,500 years ago. However, in recent decades, the population explosion, migratory phenomena and climate change have posed enormous challenges, such as universal access to water and energy resources, and especially to sanitation, the factor most closely related to human and environmental health.

Governance, economic decisions, cultural movements, the establishment of companies… everything is mostly carried out in cities. Pandemics too. In the 14th century, the Black Death that devastated Eurasia, taking the lives of at least 25 million people, mainly spread in the cities, where the physical proximity between their inhabitants, the precarious hygiene of the time, the almost total lack of sanitation and, of course, the absence of medical knowledge caused the tragedy.

In the 16th century, in what is now Mexico, smallpox, an unknown disease among the Aztecs, was introduced by the Spanish. When one of the invading soldiers became ill, he was taken to a native home in the city of Cempoallan. Soon after, the family members became ill and, within ten days, the city lost most of its inhabitants. Smallpox spread to other cities and caused a terrible death toll, which was a decisive factor in the Aztec defeat by the conquistadors.

Data to design the new “normality”

The pandemic has added new factors to human movements: fear of contagion and poverty are two of them.. © Scott Wallace / World Bank

Covid-19 urgently adds the concept of “healthy city” to the urban plans of the “sustainable city”. Health is a right that already exists in all sustainability scenarios, but the new pandemic introduces new factors that were not taken into account. Cities must not only be balanced, with the capacity to provide decent living conditions for their inhabitants without damaging the environment, but must now also ensure resistance to contagion and health responsiveness to a pandemic. Architecture and urban planning play a decisive role in redefining the “new normality” to which we must return at the insistence of politicians and the media.

In addition to health, the pandemic has had a major impact on another factor that traditionally affects approaches to the sustainability of this “new normality”: urban mobility, home-work travel, and interactions between city and rural areas, whether out of necessity, work or leisure.

The pandemic has added new factors to these human movements. Fear of contagion and poverty are two of them. An estimated 20,000 Milanese fled the city in fear when the confinement decree was announced. Something similar happened in Madrid, Barcelona, Paris and New York: thousands of citizens moved to second homes, thus increasing the possibilities of contagion. However, among those who were suddenly left without work due to the confinement, in the immense cities surrounded by slums of India and other countries, the impulse to migrate to rural areas, beyond avoiding infection, was mainly one of food survival.

In India, with the arrival of the pandemic, there was a movement towards rural areas that, beyond avoiding infection, was mainly in pursuit of food survival. © Curt Carnemark / World Bank

An increasingly urban planet

We must hurry to design new urban models because, according to World Bank forecasts, by 2050 at least two out of three people will be living in cities, and these will be increasingly larger. The latest projections suggest that by the end of the century, 11.2 billion human beings will be living on Earth, 85-90% of them in cities, making humanity an urban species for all intents and purposes.

Cities are at the center of the world, for better and for worse, and they will be so with increasing force, especially in Asia and Africa, continents that by the middle of this century will have monopolized 86 of the 100 largest cities in the world, leaving only 14 in Europe and America.

Cities are at the center of the world, for better and for worse, and they will be so with increasing force, especially in Asia and Africa. ©Peter Kapuscinski / World Bank.

The current problems of this urban planet are already serious. According to the WHO, in 2015 only 79% of the world’s city dwellers (around 3.16 billion) had direct access to drinking water in their buildings. The brunt is taken by the cities of the sub-Saharan area, where 2% of their citizens get surface water from their surroundings, that is, from rivers and lakes without the minimum guarantees of healthiness.

The situation is similar in terms of sanitation, as only 82% of the urban population had adequate sanitation in their homes. Of the remaining 18%, 10% (400 million) could only access facilities shared with their neighbors, 6% (240 million) did not have access to adequate facilities and 2% (80 million) practiced open defecation in streets and wastelands.

Which cities? Which citizens?

Living in a residential neighborhood in a European city, and one living in a shack in the putrid fishing village of Makoko, or in the miserable slums of Freetown’s hills, the healthy city concept radically changes from any point of view if extreme poverty is not taken into account. © Daniel Dinuzzo- unsplash

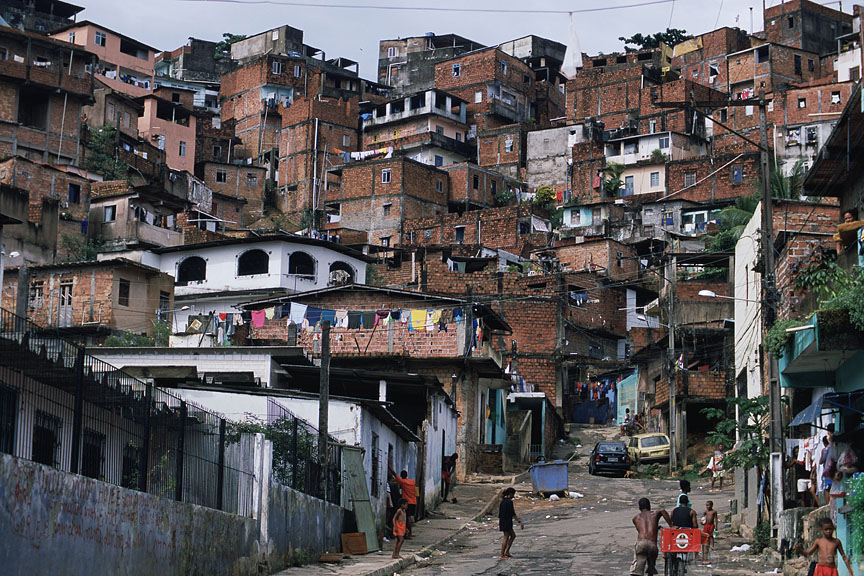

As usual, the same factor takes on a very different meaning and consequences depending on the city and neighborhood we are in. If we link the prevention of infection to a certain type of control of physical proximity, the asymmetry existing in the world in terms of housing, service infrastructure and public spaces is evident. The chances of maintaining this “social distance” are diametrically opposed between a family living in any residential neighborhood in a European city, and one living in a shack in the putrid fishing village of Makoko, or in the miserable slums of Freetown’s hills. The healthy city concept radically changes from any point of view if extreme poverty is not taken into account.

Studies on the expansion of Covid-19 also show the importance of the level of economic well-being as a differential factor. Studies in the two most important cities in Spain, Madrid and Barcelona, two of the European epicenters of the pandemic, show a lower incidence of the disease in wealthier neighborhoods. The Barcelona Public Health Agency (ASPB in Spanish) has detected 26% fewer infections in more affluent areas than in lower income areas. In Madrid, a study by its Universidad Politécnica also points to notable differences between metropolitan areas in terms of wealth.

A challenge to the smart city

This is nothing new, but this imbalance may worsen if the threat of new pandemics becomes a reality. In industrialized countries, having ensured the safety of the water cycle and the efficiency of sanitation, key factors in the control of any health crisis, tools based on mobile technologies and big data have been developed which, combined with algorithms of increasing analytical capacity, promise a high level of efficiency in the control of pandemics. Smart cities, the intelligent cities that are being designed, will be the core of these developments, and therefore avoiding the digital divide due to lack of investment becomes even more urgent. Faith in the god of technology does not anticipate solutions but always lags behind problems and the first to benefit are always those who have the economic capacity to acquire it.

The current pandemic represents a new opportunity to rethink the way we coexist in urban environments. People, who are the soul and raison d’être of buildings, infrastructure and public spaces, determine the ultimate efficiency of any urban planning or technological innovation. Modern sociology describes the inhabitants of cities as more egocentric than those of rural areas. The latter, and those who govern them, now have a new commitment that they did not have before. The success or failure of the reaction to the pandemic will depend on our capacity to advance towards the understanding and awareness that individual health is collective health, and that this, in turn, is planetary.