Aral, the lost sea, (2009) by Isabel Coixet, narrated by Sir Ben Kingsley.

A paradigm of what not to do with water

In the 1950s, the Aral Sea was the fourth largest sea on Earth with 67,300 km2, behind the Caspian Sea, Lake Superior and Lake Victoria. It was particularly rich in fish: it supplied one-sixth of all the fish consumed in the Soviet Union and its canneries exported their products worldwide.

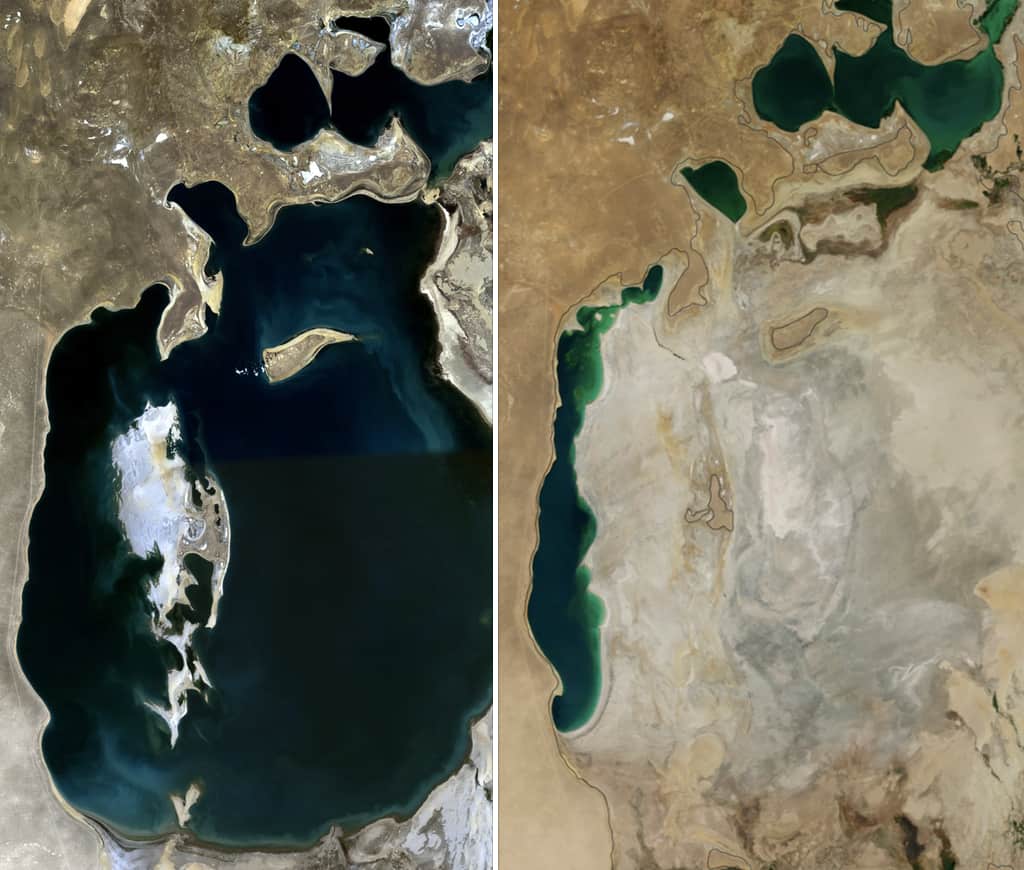

On the left, the Aral Sea in 1989; on the right, in 2014. © Earth Observatory, NASA.

The two countries sharing its coastline, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, belonged at the time to the Soviet Union. The vast steppes surrounding the lake gave the government the idea to massively develop agriculture, especially cotton farming. This was a land that was hardly suitable for these crops, as it was very arid and lacked hydraulic infrastructures for irrigation; for this reason, Soviet engineers planned to use the water of the main rivers that flowed into the Aral Sea, especially the Amu Daria and the Sir Daria. The project fostered an immense infrastructure plan based on the construction, in 1960, of a 500 km-long channel that would take one third of the water in the rivers to flood rice fields and irrigate cotton fields, one of the crops that require more water. Erroneous calculations, poor maintenance and inefficient irrigation systems caused a constant increase in the amount of water withdrawn from rives and aquifers.

At the beginning of the 1980s, when engineers realized that the amount of water reaching the lake was only 10% of the water flow in 1960, it was too late. Most of the surface had dried out and the rest was experiencing an accelerated disappearance process; in 1989, the large water body split in two, leaving one water mass to the north and another to the south, which were called North Aral Sea and South Aral Sea.

Satellite view of the degeneration of the water body of the Aral Sea, from 2000 to 2018. The dismembering of the water bodies can be observed: the north and south parts had already split up by the year 2000, later on the south part was also divided into two. That Eastern part disappeared in 2014, to resurface timidly in 2018. (Animation developed with photographs of the NASA Earth Observatory)

In 2009, when Isabel Coixet shot the documentary, the lake had already lost half of its original surface (equivalent to the island of Ireland) and its volume had been reduced to a quarter. 95% of nearby reservoirs and wetlands had become deserts and more than 50 lakes of the deltas, the most fertile areas, with a surface of 60,000 hectares, had dried out. The situation has changed very little nowadays.

Disasters with a domino effect

The loss of water triggered a series of disasters. Evaporation accelerated, as shallower lakes are easier to heat; thus, the lake entered a negative loop: more evaporation, less depth; less depth, more evaporation… Not only did the Aral Sea become smaller, evaporation also triggered salinity, causing the death of almost all fish.

In order to contain the salinity, the extraction of ground water was increased, decreasing the level of aquifers from 53 to 36 meters. Human consumption was affected: large sectors of the population ended up having no access to drinking water and the water that remained was highly polluted by fertilizers and pesticides used in cotton farming.

Fishing was ruined. The Aralsk harbor lost its water in 1970 and its inhabitants saw the sea move away day by day. The ships were stranded in a desert of salty sand, an image that became an icon of the disaster.

Isabel Coixet in the Aral Sea during the filming of Aral. The lost sea. © Jordi Azategui

On the other hand, the Aral Sea lost its capacity to regulate the climate: winters and summers became harsher and dust storms started affecting coastal regions, dragging the salt from the former seabed. The consequences on the health of the population were dramatic: diseases such as lymphatic, liver and throat cancer, anemia, chronic bronchitis, tuberculosis, typhoid fever, hepatitis and asthma shot up. Child mortality reached a rate of 7.5 per 100; more than half of these children died of respiratory diseases due to the salt and minerals existing in the dust they breathed.

Salt storms and the decrease of aquifers wiped out 40% of the vegetation in the surrounding lands and subsistence farming was no longer possible. All this caused a great migratory exodus towards more prosperous areas resulting in a demographic imbalance and cross-border problems when the Soviet Union disappeared and Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan gained their independence in 1991.

Salt and dust travelled much further, up to 200 km, reaching large farming areas in Uzbekistan, Kirghistan, Turkmenistan and other countries, reducing agricultural productivity. Salt also reached the peaks of the mountains of Kirghistan, causing the melting of glaciers which had already started due to climate change.

Will water return?

Recovering the entire ancient water body requires the cooperation of all countries whose rivers feed it. The poor political relationship between many of them has been an insurmountable obstacle to structure a project with the minimum conditions to succeed. Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan are in confrontation with Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, and the rivers Amu Daria and Sir Daria flow through these two republics, which used to be a part of the Soviet Union before its fall.

In some areas of the South Aral Sea the water is slowly returning © Mark Pitcher

Attempts to recover the Aral Sea started in 1996 when a dam was built to retain water from the Sir Daria, the river that flows into the north of the Aral Sea, to regulate the water level in this area of the lake and irrigate the surrounding land. The idea was to sacrifice the South Aral Sea to save the North Aral Sea. But the dam, built rudimentary with sand, mud and sticks, broke a few years later.

Another 13 km long dam was built in 2004, as well as several hydraulic installations on the river bed that were financed by the World Bank. The North Aral Sea increased its level by four meters in only six months, increasing its size in one third in one year and recovering part of its aquatic fauna. The most hopeful thing was to see that some of the water started timidly flowing towards the South Aral Sea (see the animation, above).

The recovery of the northern part of the lake has been favored by nature itself, which has reversed the negative loop of evaporation: water decreases to a certain volume with high salinity, slowing evaporation and stabilizing the process.

Water, once 50 km from the city of Aralsk, is now only 15 km away. The recovery of the lake is still far away, but there are already symptoms that show it is underway. Fishing is reawakening in the North Aral Sea and farming is becoming easier. Healthiness has greatly improved and anemia has decreased by 65% due to improved nutrition.

However, experts alert that full recovery continues to be extremely difficult, as many of the factors that triggered the disaster still exist. The South Aral Sea continues to lack short-term solutions and the climate crisis threatens with more droughts.

Local and international awareness of a global challenge

The disappearance of the Aral Sea is a tragedy that has fortunately transcended national and international borders in the last few years. The United Nations Development Program (UNDP) fostered an international conference on “Joint actions to alleviate the consequences of the Aral disaster: new approaches, innovative solutions, investments” in Tashkent, the capital of Uzbekistan. At this meeting, a multidisciplinary team of experts presented different ideas to attract investments and technologies to the region and to propose the best practical solutions for the Government of Uzbekistan. The conclusions of the conference were followed by the High-Level International Conference titled “Aral Sea Area – Zone for Environmental Innovations and Technologies”, held in Nukus (Uzbekistan) last October. For the first time, the president of Uzbekistan, Shavkat Mirziyoyev, presented the idea of transforming the sea into an area for environmental innovation and technologies. During what has been a true summit of heads of state to create an international fund to recover the sea, Mirziyoyev has called for common efforts to attract international investments with the aim of developing environmentally-friendly technologies, implementing a green economy and achieving the saving of energy and water. The meeting concluded with the proposal of organizing a special conference next year with the support of UNDP, the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank and the World Environmental Fund.

The ancient bottom of the Aral Sea is now a dusty desert © Phillip Capper / 2011

In the midst of fighting the climate crisis, we need to learn from one of the most severe environmental disasters caused by human activities. The environmental, climatic, economic and humanitarian consequences derived from the poor management of water are the worst menace for the global ecosystem and for the attainment of the Sustainable Development Goal 6. The Aral Sea case should be included in all school programs.