The pandemic unleashed in March 2020 was the reason why the media did not pay special attention to a disturbing scientific report published in the journal Nature a few months earlier. Titled Climate tipping points – too risky to bet against, the study points to places where certain environmental factors are degrading and may reach a dangerous “point of no return” where there is no coming back. If this were to occur, it could trigger highly destructive and difficult-to-predict climate alterations that would seriously compromise adaptation strategies and would create new and highly uncertain environmental scenarios.

The impact caused by the AR6 last August, along with a summer plagued by anomalous climatic phenomena in the northern hemisphere, has given prominence to the study, which summarizes the alerts all governments have laid on the table at the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) in Glasgow.

Most scientists accept the evidence that the Greenland ice sheet is melting at an accelerating rate. ©Kim Kenny

Nine alerts for the planet

The “point of no return” concept, often referred to as “tipping point”, is not new; it was put forward more than 20 years ago by the IPCC, which at the time warned against the dire consequences for climate if the average temperature reached 5ºC above the pre-industrial era.

In these two decades, scientists have been outlining critical areas and factors that warming was rapidly altering. As data were collected, the red alert line was lowered; in 2015 at the COP 21 in Paris, the IPCC placed it at 2ºC, to revise it shortly thereafter to 1.5ºC, which is the current reference. Coinciding with Nature’s report, the IPCC points out the high probability that these points of no return will occur if we surpass that red line.

Scientists define nine points of no return or tipping points and demand maximum attention to their evolution:

1. Melting of Arctic Sea ice

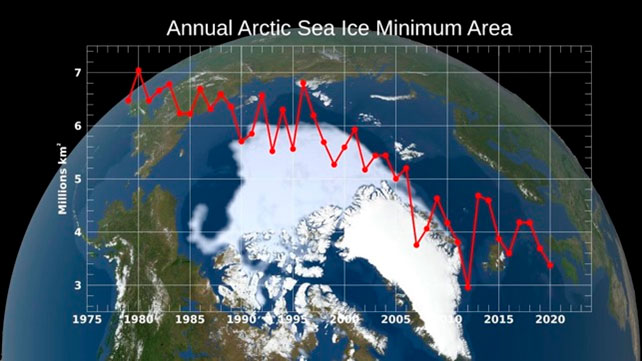

The ocean in the North Pole is warming up twice as fast as the planet’s average. The loss of ice is an eye-opening evidence that is supported by satellite images that have recently gone viral with NASA videos like this one:

Monitoring, based on satellite images, of changes in Arctic Sea ice since 1979. Every summer the ice sheet melts and reaches a “minimum” before it increases again in winter. This image shows the annual Arctic Sea ice minimum decline from 1979 to 2020, with an overlaying chart. In 2020, the Arctic Sea ice minimum covered an area of 3.36 million square kilometers. © NASA/Goddard Space Flight CenterScientific Visualization Studio. The Blue Marble data is courtesy of Reto Stockli (NASA/GSFC).

The loss of ice is of particular concern because of the dreaded “positive feedback” effect: rising atmospheric temperature causes melting, which in turn causes temperatures to rise. This is due to the fact that the exposed liquid water surface absorbs more energy from solar radiation, and therefore warms up more than ice or snow, which reflect most of this radiation, thus accelerating global warming.

2. Degradation of the Greenland ice sheet

Most scientists accept the evidence that the Greenland ice sheet is melting at an accelerating rate. Several recent studies, like Nonlinear rise in Greenland runoff in response to post-industrial Arctic warming, confirm that the ice mass has been disappearing since the mid-19th century and is now estimated to be melting about six times faster than in the 1990s. It is currently estimated to lose about 270 gigatons of ice and snow mass every year; this is the equivalent of about 110 million Olympic-sized swimming pools, which are dumped into the North Atlantic.

Greenland ice reaches a thickness of 3,000 meters at some points. If it were to melt completely, the sea level would increase by seven meters. Oceanographers estimate that if all the Arctic and Antarctic ice also melted, the global sea rise would be of 57 meters, according to a study published in 2019.

3. Retreat of boreal forests

According to Greenpeace, the forest ring around the Arctic Circle stores more than 180 million tons of carbon. Forests in Alaska, Canada, Scandinavia and Siberia play a fundamental role in climate regulation and are undergoing rapid degradation, especially worsened by the fires of the last five years. If this continues, they would reach a point of impossible regeneration as the trees will not be able to adapt to the increase in temperature.

The forest ring around the Arctic Circle stores is undergoing rapid degradation, especially worsened by the fires of the last five years. © Matt Howard- unsplash

4. Permafrost thawing

The thawing of the subsoil of the Arctic is a factor of increasing concern, as 19 million km2 of boreal and alpine land constitute an important carbon sink. The Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate, presented by the IPCC in 2019, explains that permafrost temperatures have increased to record levels since 1980, and warns that this frozen sheet in Arctic areas contains between 1,460 and 1,600 gigatons (billion tons) of organic carbon, almost twice as much as the carbon currently in the atmosphere. Its loss would accelerate global warming to unpredictable levels.

5. Alteration of North Atlantic currents

Oceanographers have detected that the so-called Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, commonly known as AMOC, is being altered as currents weaken. The most commonly accepted cause by scientists is the melting of polar areas, in particular Greenland. It is a factor that raises fears of a turning point in the water cycle with irreversible negative consequences and shows the close relationship between all the factors that determine life on Earth.

6. Loss of Amazon rainforest

The Amazon rainforest degrades due to human deforestation and droughts. A recent study has found that some areas may already be releasing more carbon than they are storing. It is estimated that the Amazon has already lost 17% of its forest since the 1970s, and recent studies warn that the point of no return could be reached after a 20% loss.

7. Degradation of warm water corals

For decades, oceanographers have been warning of coral degradation. The main cause, in addition to pollution and poaching, is the warming of seawater and its acidification, which damages their complex structures formed over thousands of years. Recent analyses indicate that they could disappear from the Earth’s seas during this century, threatening almost 25% of marine fauna, since they play an important role in its food chain.

8. Decline of the West Antarctic Ocean ice sheets

The large South Polar sea surrounding Antarctica is experiencing a similar situation to that of the Arctic: it is losing ice at an accelerated rate. A study published in Nature points out that, since 1990, nearly three trillion tons of sea ice have melted. In May, another study provided stronger forecasts regarding the red line of no return, placing it around the 2060s.

9. Loss of ice in East Antarctica

Scientists of the IMBIE project have shown through satellite observations that Antarctica lost between 2,720 and 1,390 billion tons of ice between 1992 and 2017; corresponding to an increase in the average sea level of 7.6 and 3,9 millimeters. They conclude that, if we fail to limit warming to at least the 2ºC of the Paris agreement (COP21), the South Pole continent could suffer a melting tipping point by 2060, which would almost double the sea level rise in 2100.

The Amazon rainforest degrades due to human deforestation and droughts.© Matt Zimmerman

What worries scientists the most?

The interconnection between these phenomena is what scientists are most concerned about. The possible domino effect between these critical points is evident: polar melting, for example, increases the sea level, both phenomena alter sea currents which in turn change the water cycle and the air temperature of the Amazon rainforests… and a long etcetera of uncertain phenomena. This interaction between climatic points of no return is difficult to predict and many studies are still needed, but the threat of a dystopic future is a well-founded scientific hypothesis.

Scientists also warn that there is still time to mitigate global warming, but that time is running out. COP26 in Glasgow is perhaps the most important meeting that the world’s governments have ever held in history. It must lead to real and credible commitments to curb greenhouse gas emissions. It is up to each one of us, those of us who make up civil society, to put pressure on our governments, companies and institutions to do so.