Nearly 90% of Africa’s surface water resources cross national borders. And not only political ones, but also ethnic and cultural lines within each country. This makes access to, use of, and protection of water inevitably transboundary challenges. For comparison, the figure is around 60% in the Americas and 40% in Europe. Africa’s case is therefore a critical exception.

What is the cause? Part of the answer lies in history. Colonial borders were drawn from Europe without regard for physical geography or natural water flows, splitting rivers, aquifers, and water cultures according to geopolitical interests. These imposed borders laid the foundations for persistent conflicts. The Nile crisis between Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia is a prime example.

Some of the most affected countries are also among the most vulnerable to climate change and social instability. From our fieldwork, we are aware of the situations in B Burkina Faso, Malí, Tanzania, Côte d’Ivoire, Rwanda, Uganda, and Ethiopia. All of them lie within shared basins — such as the Volta, the Niger, or the Nile — and in every local water access project, the concern for equitable distribution of water resources is clear among local and national governments.

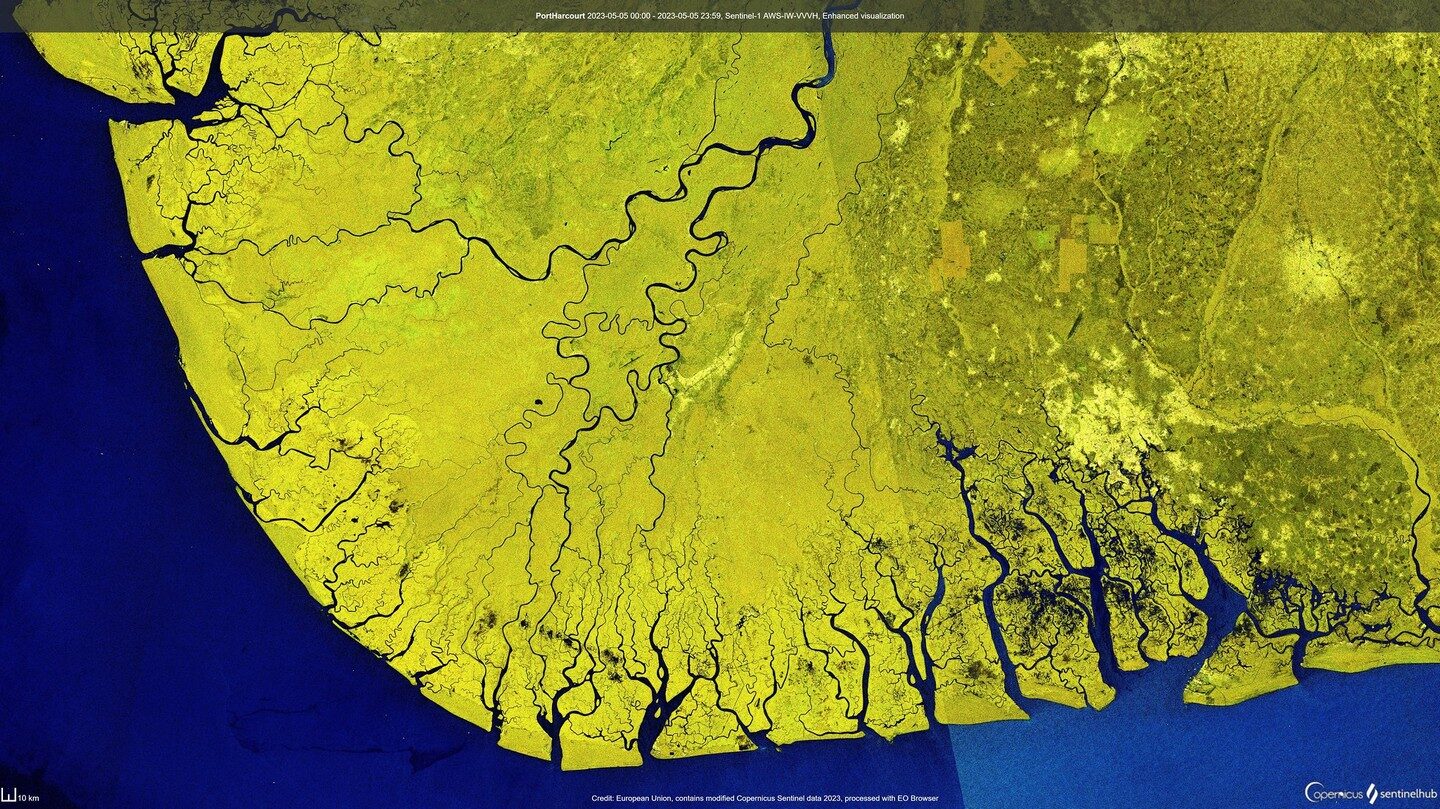

Africa is the continent with the most shared river basins in the world. © pexels-eslames

Data: The Foundation For Water Governance

Over the past decade, an ambitious institutional framework has emerged, positioning Africa’s water sustainability as a global priority.

International organisations such as the World Bank and FAO are working closely with key African mechanisms like the African Ministers’ Council on Water (AMCOW), the African Union’s Continental Water Investment Programme (AIP), and supranational authorities such as the Volta Basin Authority (VBA), which brings together the governments of Mali, Ghana, Togo, Benin, Burkina Faso, and Côte d’Ivoire.

We must move towards more just, inclusive, and evidence-based water and climate governance. Because the sustainability of any project leaves no room for ambiguity, errors become visible quickly, and infrastructure alone does not guarantee long-term universal access to water and sanitation.

The key lies in planning based on reliable, accessible, and shared data: Where does it rain, and how much? Which regions consume the most, and why? Which areas are at risk of drought or flooding? How can the effects of climate change be anticipated in regions that the IPCC has flagged for over a decade as vulnerable to recurring droughts?

These questions cannot be answered without advanced infrastructure that uses technologies for detection, visualisation, and data analysis.

We’ve previously discussed the importance of citizen participation in mapping projects and the value of satellite data to make water knowledge transparent and understandable. The current challenge is to scale this analytical capacity to the government level, so high-quality data can become the foundation for effective public policy.

Inspiring Progress

One of the most promising developments in Africa’s water data revolution is led by institutions such as the International Water Management Institute (IWMI), which coordinates technical assistance, and the Digital Earth Africa platform, which provides open access to Earth observation data in a format that is useful and accessible to governments, institutions, and communities.

As a result of this collaboration, the Digital Innovations for Water Secure Africa (DIWASA) project has become a key reference. Active in Burkina Faso, Ghana, Ethiopia, and Zambia, DIWASA uses advanced technologies such as satellite observation, water accounting, and early warning systems for droughts and floods.

Among its most advanced developments is the implementation of “digital twins” of river basins — virtual replicas based on real-world data (rainfall, flow, land use, and water quality) that enable the simulation of various management scenarios. In essence, these are hydrological simulators that help predict the effects of building a dam, altering land use, or facing an extreme event associated with climate change.

In Ghana, for instance, an online dashboard for the Volta basin allows real-time visualisation of flows, agricultural use, and water body trends. In Ethiopia, over 60 technicians were trained in 2024 on SIWA+, an innovative platform that integrates multi-scale data to design public policies more accurately adapted to local conditions.

In Ghana, for instance, an online dashboard for the Volta basin allows real-time visualisation of flows, agricultural use, and water body trends. © pexels-earthylassy

This model of evidence-based management is beginning to yield results. The next challenge is twofold: ensuring systematic adoption by governments and ensuring that the data also reaches local communities, who need it most to adapt and make informed daily decisions.

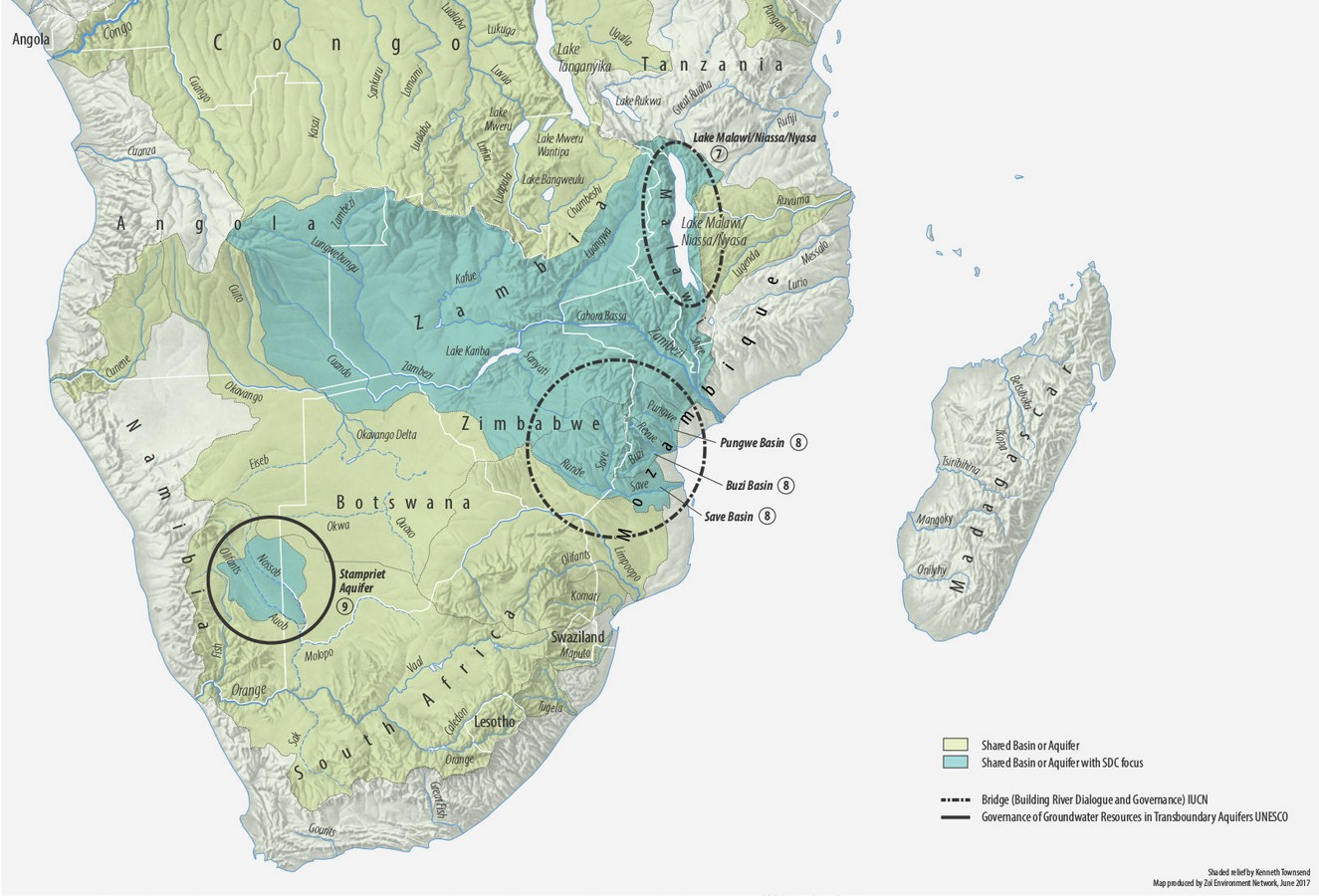

A map of the SADC (Southern African Development Community) region in Africa displaying transboundary basins and aquifers, water conflicts and cooperation. © Water and security in Africa SADC region

The Persistent Barriers of Financing and Instability

Despite technological progress, these projects require sustained investment. The recent withdrawal of funding from USAID — one of the main donors — has raised serious concerns among implementers.

Moreover, the Loss and Damage Fund agreed at COP27, meant to support vulnerable countries facing climate change, does not explicitly include the need for water data systems. This omission must be addressed at COP30 in Belém (Brazil) to ensure an evidence-based, sustainable adaptation agenda.

But the problem is not just economic. Many African countries face deep structural challenges: political instability, institutional corruption, armed conflict fueled by strategic mineral exploitation (like coltan in the Great Lakes region), and the spread of terrorist groups in the Sahel and other fragile areas.

Added to this is an increasingly complex international landscape. The growing presence of Russia and China, competing with European actors and multinationals, is reshaping cooperation agreements around water infrastructure, often prioritising strategic interests over the common good.

And above all looms climate change, acting as a risk multiplier: intensifying droughts and floods, destabilising agricultural cycles, and heightening competition over water.

Today, a silent revolution driven by data, technology, and international cooperation aims to ensure equitable access to water and more transparent governance.

The World’s Balance Flows Through Africa

Africa is key to humanity’s future, but it cannot move forward without first ensuring equitable access to water, a fundamental human right still out of reach for millions.

In this context, international alliances — the core of SDG 17 — take on special importance. It’s not just about transferring technology or financing, but about sharing knowledge, strengthening local capacities, and building trust between countries and communities.

Despite the enormous challenges, Africa’s water data revolution has begun. These initiatives show it is possible to move toward fairer, more transparent, and more effective water governance.

It is indeed a monumental task. But the water that flows in Africa affects us all.