Groundwater is the body of water below the surface of the ground. It is also commonly referred to as water in the aquifers, or simply “aquifers.” It is the invisible link in the hydrological cycle, so much of the population is not aware of the importance it has in our lives and the future of the planet. Food security, environmental balance, or the mitigation and adaptation of the climate crisis cannot be understood without the health of the waters beneath our feet. Some facts to understand its importance: this unseen water accounts for half of all drinking water, 40% of the water used to irrigate crops, and 30% of the water needed for industry.

Food security, environmental balance, or the mitigation and adaptation of the climate crisis cannot be understood without the health of the waters beneath our feet. © François/ Water Alternatives

Subsidence, a “visible” symptom for millions of citizens

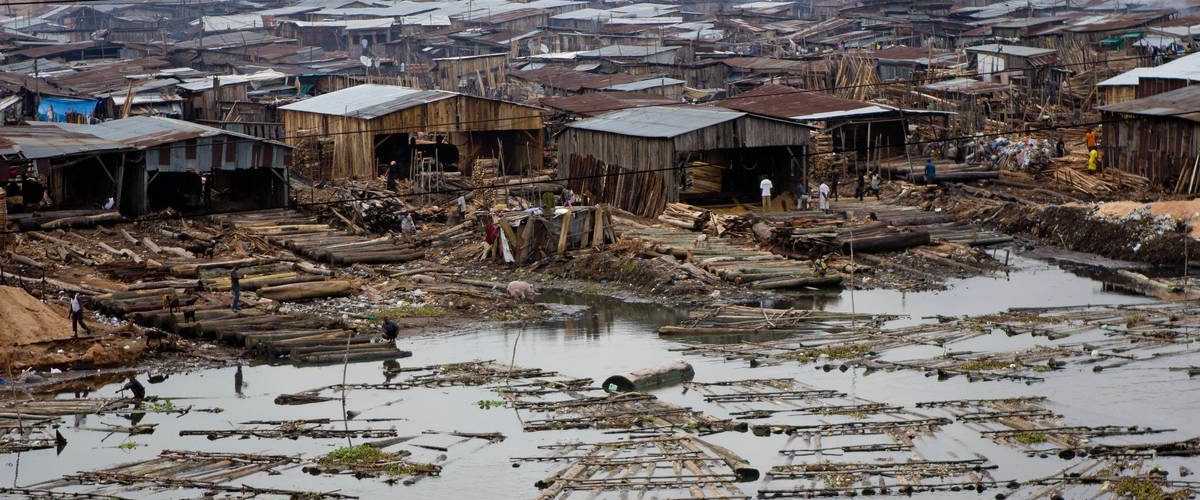

Apart from farmers, whose wells are drying up and have to be dug deeper and deeper, the population groups that have recently become aware of the diminishing volume of water in aquifers are the tens of millions of inhabitants of some of the cities above them, who are experiencing subsidence as a result. This is the so-called subsidence phenomenon, experienced in cities such as Jakarta, Houston, Lagos, and Mexico City, to name the most notable and well-known phenomena.

The population groups that have recently become aware of the diminishing volume of water in aquifers are the tens of millions of inhabitants of some of the cities above them. © Lagos, Nigeria/ Photo Stefan Magdalinski

The case of Jakarta is the most alarming as it is the fastest sinking in the world: the capital of Indonesia has gone from sinking one centimeter per year in some areas to 20 centimeters in the most affected areas, such as the north of the city. This phenomenon, mainly due to the over-abstraction of groundwater, comes on top of rising sea levels due to climate change. About 20% of the urban mass is below sea level, a figure that is expected to double by 2050. This is one of the reasons why the Indonesian government is considering replacing the capital city of around 10 million inhabitants with a new city in Borneo.

Ecosystems and food security at risk

The main threats to the world’s aquifers are overexploitation and pollution: two evils that have significantly increased in recent decades and are primarily due to the proliferation of intensive and poorly managed agriculture and livestock farming.

Overexploitation of an aquifer occurs when total water withdrawals exceed recharge. Like the one by the University of Wageningen, recent studies indicate that 20% of the underground water wells worldwide could be at risk of depletion. Two years ago, the University of Freiburg estimated that by 2050 between 42% and 79% of groundwater catchments worldwide could suffer ecological tipping points if the problem persists.

The main threats to the world’s aquifers are overexploitation and pollution, and are primarily due to the proliferation of intensive and poorly managed agriculture and livestock farming. ©Water Alternatives

The consequences of the lack of underground water or its pollution have been little researched for freshwater ecosystems, as most studies have focused on agriculture due to food security concerns. Recently, concern has also focused on evidence of the deterioration of the planet’s natural capital caused by the depletion and pollution of aquifers. Last April, the most extensive assessment of groundwater wells ever conducted by researchers at the University of California discovered that as many as one in five of the world’s aquifers was at risk of depletion. This means that millions of wells worldwide could dry up, with cascading consequences for the survival of people and ecosystems.

Pollution in addition to overexploitation

As far as groundwater pollution is concerned, intensive agriculture and livestock farming are also involved, practices that are much more common in rich countries but also in emerging economies.

Monitoring of this type of pollution is particularly intense in the European Union (EU) where, despite improvements in water quality in recent years, nitrates continue to cause groundwater pollution that is very harmful to human health and ecosystems, causing anoxia (oxygen depletion) and eutrophication (excess nutrients).

In European Community countries, between 2016 and 2019, more than 14% of groundwater continued to exceed the nitrate concentration limit set for drinking water. And this underground degradation also affects the rest of the water. According to observations, water declared eutrophic in the UE covers 81% of marine waters, 31% of coastal waters, 36% of rivers, and 32% of lakes.

A classic example is the case of mega pig farms: the manure produced by these animals is stored in tanks and then spread on neighboring fields as fertilizer mixed with water (slurry); when the soil cannot absorb any more, the excrement leaches into the groundwater and contaminates it with nitrates.

In Spain, other ecosystems are suffering similar situations, such as the Tablas de Daimiel wetland, which has seen its surface water diminish due to overexploitation of aquifers.© Santiago López Pastor

Nefarious cases to learn from

An example of the nefarious consequences of poor agricultural practices on groundwater and the marine environment is the sadly famous disaster of the Mar Menor, Europe’s largest salt marsh in the region of Murcia in south-eastern Spain. All the elements converging in the destruction of aquifers and their consequences on the water cycle and the environment have converged there: poor land management, adoption of intensive agriculture with high fertilizer use, water irresponsibility, inefficient governance, and underestimation of scientific reports that for years warned of the danger.

In Spain, other ecosystems are suffering similar situations, such as the Tablas de Daimiel wetland, which has seen its surface water diminish due to overexploitation of aquifers. In 2009, the swamp was so dry that fires broke out in the peat subsoil. Its contamination by phosphates and other chemical fertilizers is now one of the highest among European ecosystems. Also, in Spain, a country that has accumulated EU environmental sanctions and warnings, the Doñana National Park, a mosaic of ecosystems home to unique biodiversity in Europe, is endangered by the overexploitation of its aquifers due to intensive agriculture.

Similar situations occur in agricultural areas that overexploit groundwater. In Baja California (Mexico), over 37% of aquifers are highly extracted, the most critical being the Mexicali aquifer. In India, the aquifers in the upper Ganges basin are losing water at an alarming rate. Across the country, a 2016 World Bank report claimed that groundwater extraction for agricultural use had increased sevenfold in the last 50 years. In US California, recent droughts last summer left agriculture without groundwater for irrigation in its valleys. The state’s entire agricultural industry faces the uncertainty of a future in which climate change won’t help.

How can groundwater be saved?

Implicit in the problems identified are the solutions. The dangers of overexploitation will worsen with the increase in droughts caused by the climate crisis. A universal measure is the proper management of agricultural land, avoiding intensive agriculture where there is not enough water. This measure requires a considerable effort in governance, as it almost always involves long-standing and deep-rooted socio-economic structures. On the other hand, irrigation efficiency must be increased, especially in economically poorer countries that do not have adequate technology to monitor the state of aquifers and water transport. Adopting the best drip irrigation systems powered by renewable energy must be encouraged. Meanwhile, with harsh legislative measures, nutrient pollution must be fought to enforce regulations and promote a return to traditional agriculture with nature-based solutions.

The regeneration of aquifers also requires the adoption of community-based solutions. Some of these solutions are ancestral and forgotten, such as constructing small reservoirs in India, a country with a deep knowledge of groundwater. Over millennia, its people have developed ingenious structures to efficiently use and replenish water in shallow aquifers and distribute it in a balanced and efficient way among the population. The current government agrees that this ancestral knowledge must be the basis for the country’s aquifers to become a reliable local resource, especially when the monsoons fail, a circumstance that worsens year after year.

Our experience in constructing the Ganjikunta and Girigetla reservoirs and the more recent Settipalli and D.K.Thanda4, projects in which we have collaborated with the Vicente Ferrer Foundation, shows that dammed water, when filtered, makes it possible to regenerate aquifers that supply water to the wells in the area and improve reforestation, something essential to stop the aggressive erosion experienced by the region and which degrades the land to the point of making it unproductive. This allows farmers to overcome the dry spells between monsoons and diversify their crops.

The theme of World Water Day 2022 – “Making the visible invisible” – must literally serve its purpose. Suppose all the world’s inhabitants are aware of the existence of the water under our feet. In that case, we can make progress on solutions that are not always easy to adopt, such as those aimed at regulating intensive agriculture and livestock farming, but which are essential for food security and environmental balance.