Of all the nomadic people that populate the Sahel, the Fulani are the most numerous since the 12th century. They are estimated to reach 40 million across the African continent, making them the largest nomadic ethnic group in the world today. Their origin is controversial: some theories place them on the banks of the River Nile; others refer to the result of a crossbreeding between the people from southern Sudan and nomads from the Sahara; there is also the hypothesis that they entered Africa from the Caucasus or even from the south of the Arabian Peninsula. However, there is majority consensus among ethnologists that the present-day Fulani are the result of various mixtures with other ethnic groups.

The Fulani’s ancestral methods of pastoralism, agriculture and food production in the sub-Saharan strip, and their deep-rooted sense of solidarity are the basis of their resilience. © Arne Hoel / World Bank

The wisdom of endangered transhumance

Like all nomadic people, the Fulani have a close relationship with water. Mainly devoted to shepherding through transhumance between the north and the south, depending on the rainy seasons, they have acquired a very fine climatic sense and an exact knowledge and care of the water points and natural resources provided by nature. One of them is the baobab, a tree capable of storing more than 130,000 liters of water to survive during the dry season.

While Fulani have to manage the water sources precisely, at some point along the route, they need to travel up to 10 kilometers, a task that is usually carried out by women, while men take care of the cattle.

Every year, at the first signs of drought, at the beginning of November, as soon as rivers start to dry up and pastures become scarce, families leave the northern regions behind and move south, travelling by wagon for one or two months. When the first rain comes in June, they return to the north. But climate change is affecting them in recent years. In 2020, the drought in the north caused the pastures to turn yellow earlier, especially in the western Sahel (Senegal, Mali and Burkina Faso), and shepherds had to bring forward their departure to October.

While on the move, they have to manage the water sources precisely to regularly fill the jerry cans they are carrying. This means that, at some point along the route, they need to travel up to 10 kilometers, a task that is usually carried out by women, while men take care of the cattle.

An efficient economy beset by violence and bad governance

The Fulani, like most nomadic people in the Sahel, have experienced the ups and downs of the region due to the imbalances caused by colonial extractivism and the ethnic and religious wars that followed. Despite this, in recent decades they have shifted their economy from the exchange of meat products and milk for vegetables and fruit from other farming people, which was their main activity during the 20th century, to an efficient trade based on the use of their ancestral adaptive abilities to the Sahel climate in their dairy production methods.

Women are the backbone of this economy. They are the ones to decide how much milk will be destined for the family and how much will be used to breastfeed the offspring. Women also process the milk according to the seasons. In the humid season, they make butter and soft cheese they cut into cubes and fry. With the excess whey they make a liquid called nono which, in the dry season, they mix with the water retained by the baobabs and their fruits to ferment it and obtain a very nutritive drink, similar to kefir, which can last for several days in the high temperatures of the region.

A model that must endure and develop

This Fulani economy has recently been highly valued by UNESCO for being an example of sustainability and is becoming a model in many regions of the Sahel to face the uncertainty of climate change and try to root pastoral communities to avoid migration to the cities of the south.

The World Bank is developing the USD 248 million Regional Sahel Pastoralism Support Project (PRAPS), which operates in transhumance corridors based on support for women, animal vaccination, the creation of water supply posts, the creation of new livestock markets and the creation of committees for conflict resolution. This last aspect has an inter-state approach with the aim of achieving effective cooperation between governments, a basic issue hindered recently by the increase in ethnic and terrorist violence endemic to the Sahel.

Fulani suffer from the shortages of rural communities and often lack improved sources and are forced to collect surface water.

The incidence of coronavirus and the abandonment of transhumance

The restrictions of the Covid-19 pandemic were a blow to the transhumance economy. According to the World Bank, livestock farming is the livelihood of more than 20 million people in the Sahel, who migrate every year in search of pasture and water. The pandemic has severely affected them as markets for livestock and dairy products were closed and travel in search of pasture and water was banned. These governmental restrictions coincided with the harshest months of the dry season and many shepherds have been obliged to spend what little money they had on fodder for their animals.

The pandemic has therefore accelerated the abandonment of shepherding, which started years ago due to climate change and insecurity. Many Fulani have settled in rural communities. There they have other problems with water: they suffer from the shortages of rural communities, which do not have access and often lack improved sources and are forced to collect surface water. This is the case told by the Nigerian Jefferson Japheth Aku in his short film Hope, finalist at the We Art Water Film Festival 5.

The short film Hope by Jefferson Japheth Aku, finalist at the We Art Water Film Festival 5 in the micro-documentary category

The short film narrates the everyday life of Maimuna and her sisters. When they wake up every morning, before going to school, they go to the river to get water. They must walk and waste hours before reaching the river bank. During the dry season there is no water and they are obliged to dig a hole in the ground to get it, but the water is always dirty and unsafe to drink.

This case is similar to that of most women in rural areas in Africa, who are victims of the lack of water and poor sanitation. This small community does not have any water, toilets or latrines. They are obliged to defecate in the open, with the health, safety, dignity and environmental degradation problems this practice entails.

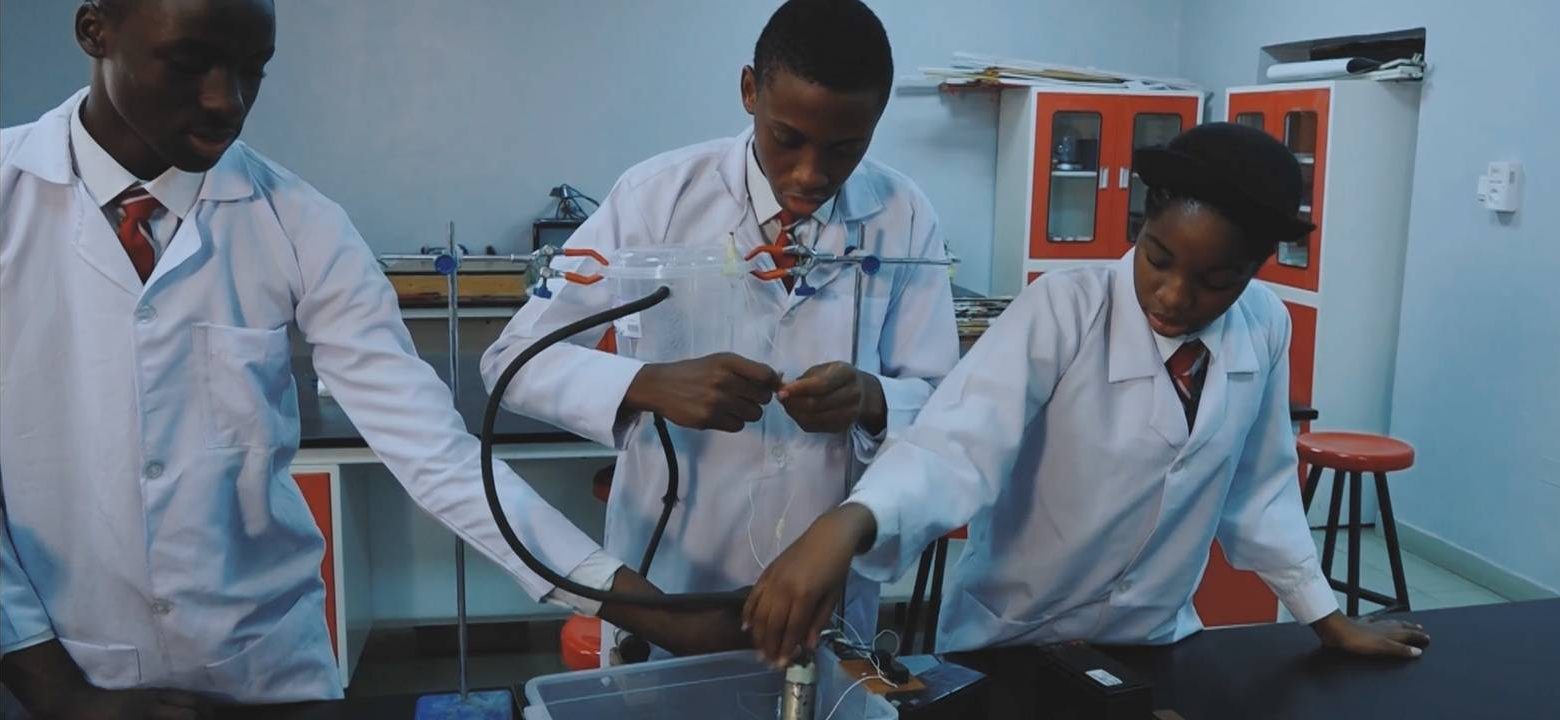

The short film also shows the awareness the lack of water in rural communities is raising among schoolchildren in Nigeria. A project by secondary school students in Abuja, the capital, is based on the use of recycled materials to manufacture a solar-powered water pump. The awareness of the water access problems in the Sahel is growing across sub-Saharan Africa. Solving them is vital for tackling climate change. Safeguarding ancestral traditions of agriculture and livestock farming is a necessary condition both in the Sahel and in the rest of the poor rural world in order to stop migration due to poverty and environmental degradation and achieve planetary sustainability. The Agenda 2030 depends on it.

A project by secondary school students in Abuja, the capital, is based on the use of recycled materials to manufacture a solar-powered water pump.